Acknowledgement Statements: A First Step in Reconciliation

Kenneth Favrholdt

Every place in Canada, from north to south, east to west, has an Indigenous history, from the largest cities to the smallest villages. Acknowledgement statements, called land, territorial, or treaty acknowledgements, are increasingly used by museums as a way of connecting museum’s physical presence with the Indigenous geography of its location, and paying respect to original inhabitants who may or may not be reflected in a museum’s collections. The acknowledgements can take many forms — statements on entrance signs, in exhibits, websites or other social media platforms and oral statements at events and programs offered by museums.

In a CBC News article, “What is the significance of acknowledging the Indigenous land we stand on?,” which can be read online, Alison Norman, a research adviser for the Ontario Ministry of Indigenous Affairs, states that with the release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) Calls to Action in 2015, land or territorial acknowledgements have become increasingly common in non-Indigenous spaces in the last few years. The TRC’s Calls for action do not mention a need for acknowledgement statements. Yet their use has been stimulated by land claims and the assertion of treaty rights over many decades.

Land acknowledgment is a practice that pre-dates contact with Europeans. Shylo Elmayan, Anishinaabe from Hamilton and McMaster University’s director of Indigenous student services notes that, “It [acknowledgement] happened at ceremonies, or when one tribal member would light a small fire on the outskirts of territory he was visiting, wait for someone to meet him, smoke a peace pipe, acknowledge whose land it was, discuss intentions. It’s an Indigenous protocol, we’ve always done that… but now everyone is noticing it because non-Indigenous organizations are saying it.”

This is not to say that non-Indigenous organizations shouldn’t put time into land acknowledgements. Dawn Saunders Dahl, Indigenous Program Manager at the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies, believes that acknowledgements should be given by non-Indigenous staff or representatives, not spokespersons of the local Indigenous group:

“In my opinion, land or territorial or treaty acknowledgements are for those who are not Indigenous to declare. Indigenous peoples know whose land they are on. Acknowledgements are for newcomer/settler inhabitants to provide an awareness of Indigenous presence and land rights, and to recognize privilege. These acknowledgements can start by being stated in everyday life at public events, and in marketing materials such as email signatures, websites, and signage.

Indigenous peoples can, and should, be invited to provide welcome messages, but should not be the ones holding the responsibility of declaring whose traditional lands they currently occupy.”

Research by museums is important to find out more about their Indigenous collections and the history of Indigenous peoples in their area. Recently, Canadian Geographic published the Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada which provides a comprehensive overview with maps showing the languages spoken, treaty lands, and reserves across the country. For example, in Alberta there are approximately 258,000 Indigenous people comprising 45 First Nations and 140 reserves within three treaty areas, eight Métis settlements, and Inuit (see also link to map by the Alberta Teachers’ Association, “We Are All Treaty People” and Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada for a comprehensive list of First Nations in Alberta).

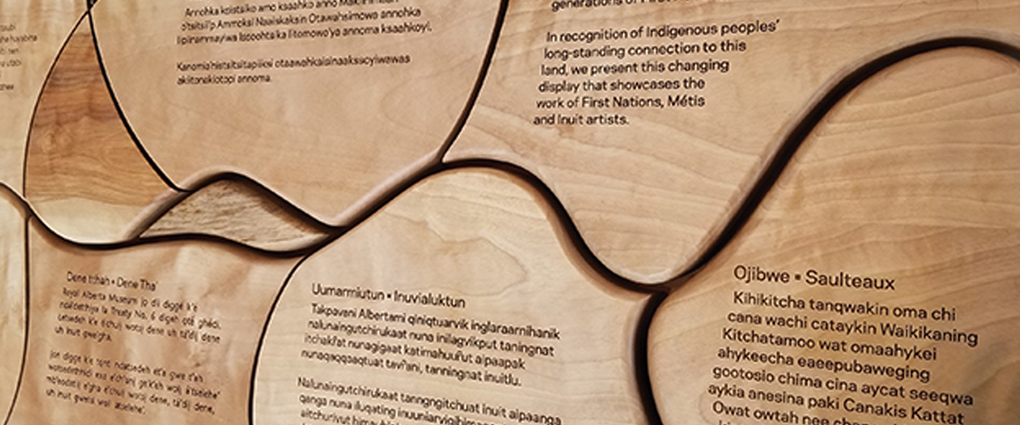

After extensive consultation with Indigenous groups and to reflect the diversity of Indigenous people represented by their collection, the new Royal Alberta Museum in Edmonton presented a statement in 15 languages, on a panel which welcomes visitors to the museum and “respectfully acknowledges that the land upon which we stand is Treaty Six Territory and a meeting place for generations of First Nations, Métis and Inuit.”

There is great variety to acknowledgements across Canada, as diverse as the Indigenous peoples of the country and the land itself, and contact with local Indigenous organizations is vitally important in creating a meaningful acknowledgement statement. How can the museum best work with local Indigenous groups? Too often in the past, the decisions of museum boards or directors have superseded the input of Indigenous peoples in presenting their own culture.

Most First Nations in British Columbia stand on unceded territory. The Royal British Columbia Museum (RBCM) in Victoria, clearly emphasizes the fact that, although small treaties were made in the 1850s, the Museum stands on the traditional territory of the Lekwungen (Songhees and Xwsepsum) Nations. Director Jack Lohman notes that an acknowledgement is prominently displayed in the main lobby, on the museum’s website, on the signature lines of employee e-mails, on press releases, and on the Museum’s publications. The museum’s verbal acknowledgement has gone back more than two decades. States Lohman, “The RBCM is guided in Indigenous matters by the Indigenous Advisory and Advocacy Committee which includes the Chief Councillor of the Songhees Nation.”

To the east, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan is home to the Remai Modern. Earlier this year, a permanent land acknowledgement was installed in the atrium of the building. While currently only in English, the word “welcome” is in six different Indigenous languages above the lobby fireplace and Cree syllabics reference the Museum’s location as part of signage at the entryway. Indigenous Relations Advisor Lyndon J. Linklater also indicated that as part of the overall strategic plan, an Elders Advisory group will be created that will assist the museum on Indigenous issues.

Meanwhile, the Manitoba Museum in Winnipeg has had a long relationship between Indigenous peoples and the staff of the museum. Here, the first of the numbered treaties, Treaty 1, was signed in August 1871 between Canada and the Anishinabek and Swampy Cree of southern Manitoba. The area is also part of the Métis homeland. The museum has focused on the historic Treaty 1 as the cornerstone of its interpretation and protocol for Indigenous acknowledgement. French translation is also provided and a series of optional scripts have been created for use at different events, including Indigenous, mixed, or non-Indigenous with a pronunciation guide for the various nations. Their website states:

“The Manitoba Museum is located on Treaty 1 land, and the homeland of the Métis Nation. These lands, occupied for thousands of years, are the traditional territories of the Anishinaabeg, Ininiwak, and Nakota Nations. The Museum is committed to collaborating with all Indigenous peoples of this province including the Dakota, Anishininiwak, Dene, and Inuit.

We acknowledge the harms of the past, are committed to improving relationships in the spirit of reconciliation and appreciate the opportunity to live and learn on these traditional lands in mutual respect.”

But not all museums have created and communicated an acknowledgement statement, and some institutions are grappling with doing so or do not feel the need to. Some people feel acknowledgement statements have become too rote and superficial. Universities and colleges are experiencing the same discussion around the issue.

Hayden King of Ryerson University, located on the territory of the Haudenosaunee, the Anishinaabek, spoke to CBC Radio’s Unreserved host Rosanna Deerchild about territorial acknowledgements in June 2018:

“I started to see how the territorial acknowledgement could become very superficial and also how it sort of fetishizes these actual tangible, concrete treaties… I’d like to move toward a territorial acknowledgement where you provide people with a sort of framework and then let them write it themselves. The really important aspect of a territorial acknowledgement for me, anyway, is this sort of obligation that comes on the back end of it.”

Guelph Museums is one of many other museums that have espoused reconciliation in their acknowledgement by making a commitment to the TRC’s calls to action. They state on their website:

“Land acknowledgments are crucial in sustaining awareness and remembrance; however, they require action and participation in order to fulfill a purpose. We each hold responsibility for participating in this process as we are all treaty people...

“We are adjusting the way history has been portrayed at the Museums to incorporate authentic Indigenous voices, stories, and knowledge, which have traditionally been sidelined in favour of colonial narratives.”

Hopefully this article has been helpful in providing a bit of an overview of the topic of land acknowledgements, some helpful samples and ideas of what some museums in Canada are doing, and in increasing museums’ confidence to start a conversation with Indigenous communities in their area.

In every acknowledgement, it should be emphasized, reconciliation with Indigenous peoples is the goal. It is the starting point for a discussion on actions that museums can undertake, to recognize the ruinous history of relationships with Indigenous peoples. This, then, is the challenge for museums: to respectfully engage with Indigenous peoples — which may be a long process, considering the legacy of colonization that they have experienced. But a simple but profound acknowledgement — that we are all living on Indigenous land with a shared history we cannot ignore — is a start.

Kenneth Favrholdt is an historical geographer with long experience as a curator in community museums, and also teaching geography. Most recently Ken was Executive Director of the Claresholm & District Museum, Alberta. Currently he works as a freelance writer and heritage consultant researching Indigenous and early settler themes in Western Canada. His special interest is early cartography and historic trails of the West. Ken lives with his wife Linda in Kamloops, BC.