Value Study of GLAMs In Canada

Report for the Ottawa Declaration Working Group

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Operating Costs of GLAMs

- Operating Revenues of GLAMs

- Value to GLAMs’ Physical Visitors

- Non-use Value

- Online Value

- Formal Education

- Wider Benefits

- Qualitative Social Benefits: Multi-criteria Analysis

- Conclusion

- Appendix 1 Economic Welfare Approach

- Appendix 2 Valuing Glam Visits

- Appendix 3 Online Value

- Appendix 4 Wider Benefits: Wellbeing

- Appendix 5 Other Wider Benefits

- Appendix 6 Questionnaire

- Appendix 7 Descriptive Statistics on Questionnaire

Oxford Economics

Oxford Economics was founded in 1981 as a commercial venture with Oxford University’s business college to provide economic forecasting and modelling to companies and financial institutions. We have become one of the world’s foremost independent global advisory firms, providing reports, forecasts and analytical tools on more than 200 countries, 250 industrial sectors, and 7,000 cities and regions.

Headquartered in Oxford, England, with regional centres in New York, London, Frankfurt, and Singapore, Oxford Economics has offices across the globe. We employ more than 250 professional economists, industry experts and business editors—one of the largest teams of macroeconomists and thought leadership specialists. Our global team is highly skilled in a full range of research techniques and thought leadership capabilities, from econometric modelling, scenario framing, and economic impact analysis to market surveys, case studies, expert panels, and web analytics.

Oxford Economics is a key adviser to corporate, financial and government decision-makers and thought leaders. Our worldwide client base now comprises over 1,500 international organizations.

Research leads on this report

Andrew Tessler, Associate Director

Andrew joined Oxford Economics in 2007 and heads up the Australian office. He has worked on a wide range of economic studies while at Oxford Economics, including economic appraisals and valuations, economic impact studies, and market analysis.

atessler@oxfordeconomics.com, + 61 2 8458 4224

Alice Gambarin, Senior Economist

Alice joined Oxford Economics in 2014, and has since gained experience in economic impact studies, including for a number of Higher Education institutions, as well as in social return on investment studies.

agambarin@oxfordeconomics.com, + 1 646 503 3054

Stephanie Lukins, Senior Economist

Stephanie is a Senior Economist at Oxford Economics who focuses on quantitative analysis. She has skills in developing deep quantitative skills, integrating econometrics and stated preference methods.

slukins@bisoxfordeconomics.com, + 61 2 8458 4230

Oxford Economics, 5 Hanover Sq, 8th Floor, New York, NY 10004.

Tel: +1 646-786-1879 Web: www.oxfordeconomics.com/consulting Twitter: @OxfordEconomics

This report is confidential to the Ottawa Declaration Working Group and may not be published or distributed without its prior written permission. The modeling and results presented here are based on information provided by third parties, upon which Oxford Economics has relied in producing its report and forecasts in good faith. Any subsequent revision or update of those data will affect the assessments and projections shown.

Foreword

Canadian galleries, libraries, archives and museums ( GLAMs) form an integral part of the fabric of our nation, enriching the lives of millions of visitors of all ages, backgrounds and regions every year.

Rich repositories of art, information, history and treasure, these precious institutions serve to preserve and promote Canadian heritage at home and abroad, while providing access to resources for education, research, learning and artistic creation.

Collectively known as the GLAM sector, ours is an industry that regularly punches above its weight. Non-profit GLAMs, whether in large cities or small towns across the country, attract world-class exhibits and provide communities with essential educational and research opportunities they may not otherwise be able to access.

For too long, members of the GLAM sector have largely operated in silos. Enter the Ottawa Declaration Working Group, comprised of sector representatives and co-led by Library and Archives Canada ( LAC) and the Canadian Museums Association ( CMA). We now recognize the importance of working together to increase the understanding of the value of our sector. We believe this first-of-its-kind study goes a long way towards that goal.

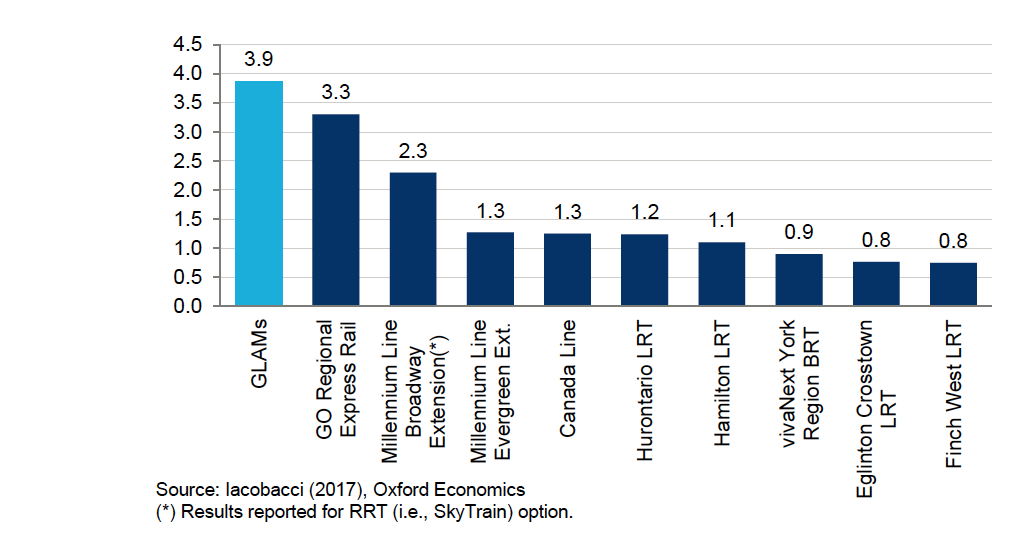

An initiative of the Ottawa Declaration Working Group comprised of sector representatives and co-led by the Canadian Museums Association ( CMA) and Library and Archives Canada ( LAC), the study found that for every dollar invested in non-profit GLAMs, society gets nearly four dollars in benefits. This return is on par with government investments in transportation infrastructure projects.

The study was conducted by Oxford Economics using metrics commonly employed by cultural institutions, as well as the results of a national survey of Canadians. It found users of GLAMs would be willing to pay $4 billion more per year to access them if required – a testament to the intrinsic value of GLAMs to Canadians.

This is a value so great, that even non-users recognize the importance of GLAMS to society at large and to future generations. Non-users said they’d be prepared to contribute $22 per year for museums, $17 for galleries and libraries and $14 for archives as a donation towards the maintenance of these institutions. This amounts to an additional $2.2 billion per year.

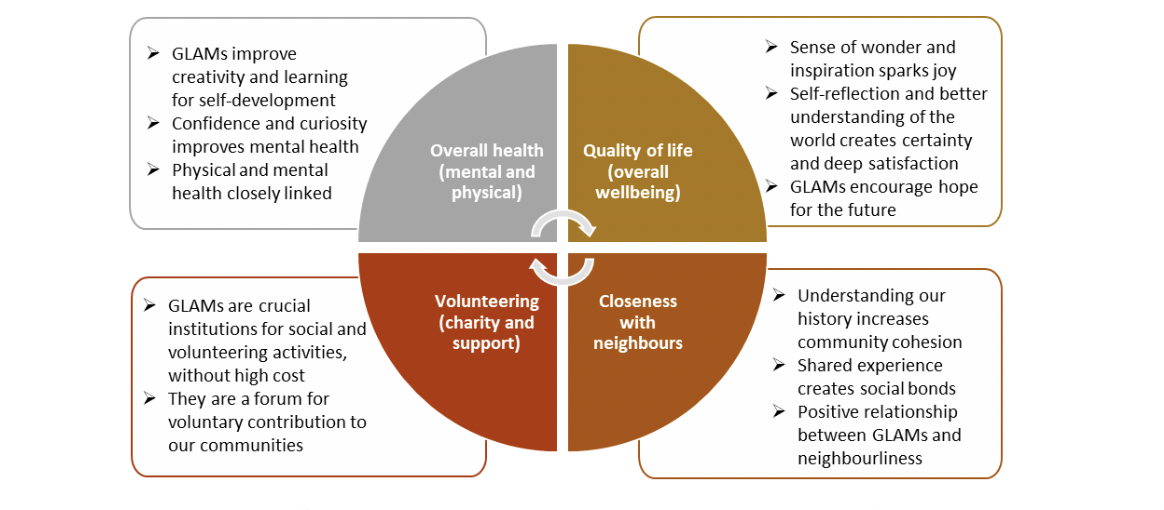

In all, 96% of respondents surveyed for the study said that museums contribute to our quality of life. Indeed, the study found that visiting GLAMs can be linked with improved health and wellbeing – equivalent to receiving a monetary bonus of $1,440 a year.

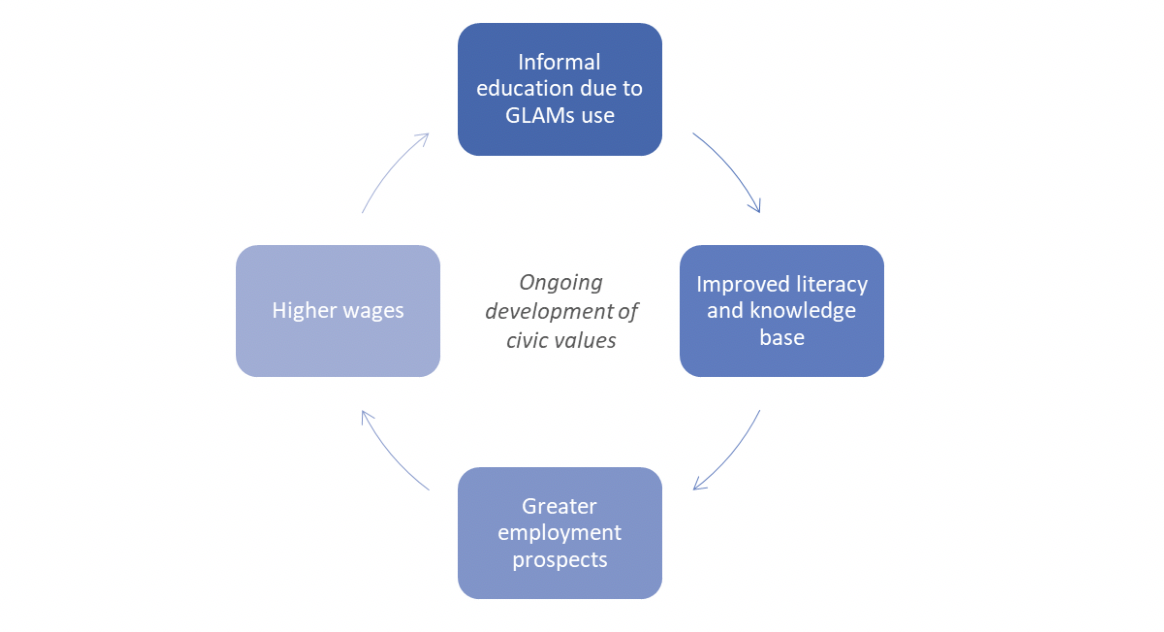

GLAM visits are associated with many other important societal benefits including greater literacy, curiosity, innovation, knowledge and creativity, increased rates of volunteerism and a better sense of community. These are incredibly important qualities in an increasingly divisive world.

Another way for users to interact directly with GLAMs is through their official websites, online catalogues and social media pages. The study pegged the value of these online visits at $1.6 billion per year.

It also noted GLAMs generate significant educational benefits for Canada, including through school visits which provide children across the country with important learning opportunities. The value of these visits is estimated at $3.1 billion. It was further found that academic libraries contribute an additional $3.4 billion and are associated with higher student wages and income over the working lifetime of students.

In all, it is estimated that society gains nearly $8.6 billion from GLAMs’ existence every year. That is no small contribution to Canada’s economic and social prosperity. Accordingly, the preservation, promotion and development of GLAMs should be of concern not just to those of us who work in the sector, but to all Canadians.

Ottawa Declaration Steering Committee

Jack Lohman, Royal BC Museum and President of the Canadian Museums Association, co-chair

Leslie Weir, Library and Archives Canada, co-chair

In alphabetical order:

Loubna Ghaouti, Université Laval

Paul Gilbert, Calliope Consulting

Anne-Marie Hayden, Canadian Museums Association

Chris Kitzan, Canada Aviation and Space Museum

Christine Lovelace, University of New Brunswick

Maureen Sawa, Greater Victoria Public Library

Vanda Vitali, Canadian Museums Association

Executive summary

In 2016, the Canadian Museums Association ( CMA), in partnership with Library and Archives Canada, held a summit on the value of galleries, libraries, archives and museums ( GLAMs). Oxford Economics participated in the discussion, recommending that “the broad [ GLAM] community should consider actively working together to collect data and to carry out horizontal value studies.” In late 2018, the CMA, on behalf of the Ottawa Declaration Working Group, commissioned Oxford Economics to undertake a national study looking at the value of GLAMs in Canada.

150 million

Estimated visits to Canadian galleries, libraries, archives and museums in one year. Of these, over 100 million were to public libraries and over 30 million to museums.

Canadian GLAMs receive in the region of 150 million visits every year, but they are much more than simply visitor attractions. They preserve and promote Canadian heritage domestically and around the globe, while providing access to resources for education, research, learning and artistic creation. This report aims to capture the fundamental role played by non-profit GLAMs in Canada, using a combination of quantitative value metrics and qualitative assessments of societal values.

How we assess the value of galleries, libraries, archives and museums

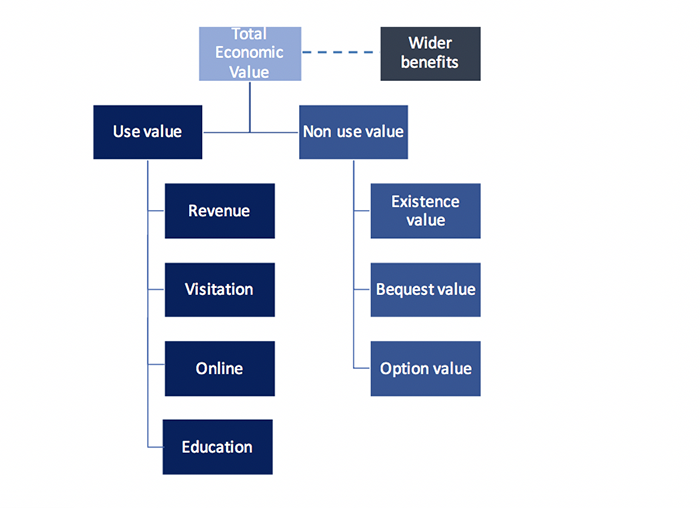

This study provides an assessment of the value of GLAMs using cost-benefit analysis ( CBA) within an economic welfare framework.Footnote 1 It takes a Total Economic Value ( TEV) approach, which measures the economic benefits accruing not just to direct beneficiaries such as GLAMs visitors, but to “non-users”—people who value GLAMs’ existence even if they have not recently visited one.

While assessing the costs of maintaining and operating GLAMs is relatively simple, quantifying the benefits is more difficult, requiring a range of economic techniques in line with the diversity of activities GLAMs undertake. These include a calculation of their value as visitor attractions—computed from what visitors actually pay to access GLAMs, but also an estimation of what visitors would have been prepared to pay over and above the ticket price (known as the “consumer surplus.”)

$4.0bn

Total annual “consumer surplus” of visitors to GLAMs in Canada. This is the sum of the additional amounts these visitors would be willing to pay to visit GLAMs .

To capture the non-use and broader social value of GLAMs, we undertook a national survey of 2,045 Canadian residents (hereafter referred to as the “national survey.”) Willingness to pay questions were incorporated in this survey, and quotas were imposed by sex, age, education, language (English/French), and province and territory of residence to ensure a representative sample of the Canadian population.

Value of GLAMs to their visitors

Based on the most current data, an estimated 150 million visits are made to GLAMs by members of the public each year. Some visits required an entry fee, and hence produced operational revenues for the institution. For many others, such as libraries, entry was free of charge.

Researchers use a variety of approaches to estimate the value visitors place on GLAMs. The approach adopted for physical visits in this study is the Travel Cost Method ( TCM), which estimates consumer surplus based on how demand would change if the costs of admission were to rise from current levels. This approach suggests a total physical use consumer surplus for GLAMs of $4.0 billion over a one-year timeframe.Footnote 2

$1.6bn

Total one-year value of GLAMs’ online services. The introduction of online services has seen much greater access to GLAMs information in recent years.

Non-use value of GLAMs

Beyond visitor benefits, another category of valuation represents the underlying values which Canadians hold for GLAMs whether or not they visit them. This represents the fact that, regardless of whether they visit them, Canadians value these institutions and want them to be supported. This so-called non-use value incorporates a number of components, including:

- the value that people attach to the existence of GLAMs whether or not they will ever visit them (existence value);

- the value placed on preserving GLAMs for the benefit of future generations (bequest value); and

- the value of having the option to visit GLAMs at some point in the future (option value).

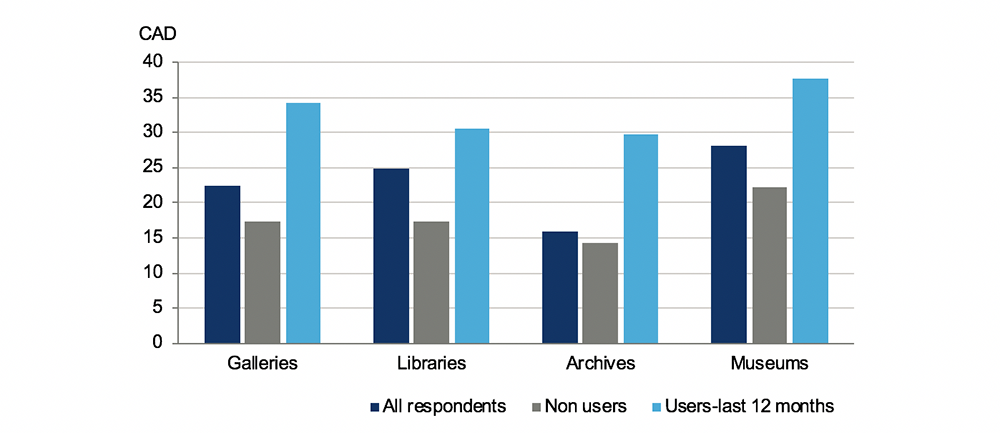

To quantify these intrinsic values, our national survey explored the maximum amount people would pay each year as a donation to maintain all of Canada’s non profit GLAMs. Respondents who did not visit GLAMs over the past 12 months stated they would be willing to contribute $22 per year for museums, $17 for galleries and libraries, and $14 for archives. Taking these values as an underlying non-use value of GLAMs for all Canadians 16 and above, we estimate a total non-use value of $2.2 billion for the entire GLAM sector in Canada.

$3.1bn

Total educational benefits to school students. This is the value of GLAMs’ educational contribution to the students and society as a whole.

Educational value of GLAMs to students

GLAMs also generate significant educational benefits for Canada, including the learning that school visits provide to children across the country. While estimating returns to education is not straightforward, economists have long recognized and measured such returns as the value that education contributes to future wages.

We adopted this method to calculate a total value for GLAMs’ educational benefits (as a result of school visits) of $3.1 billion.

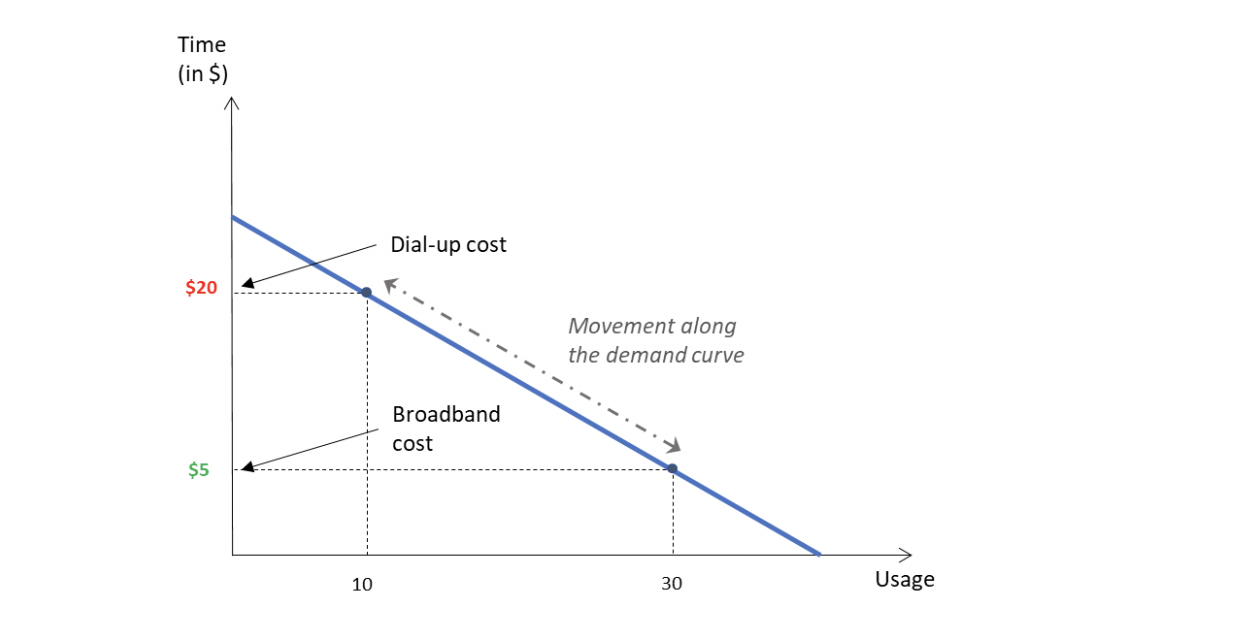

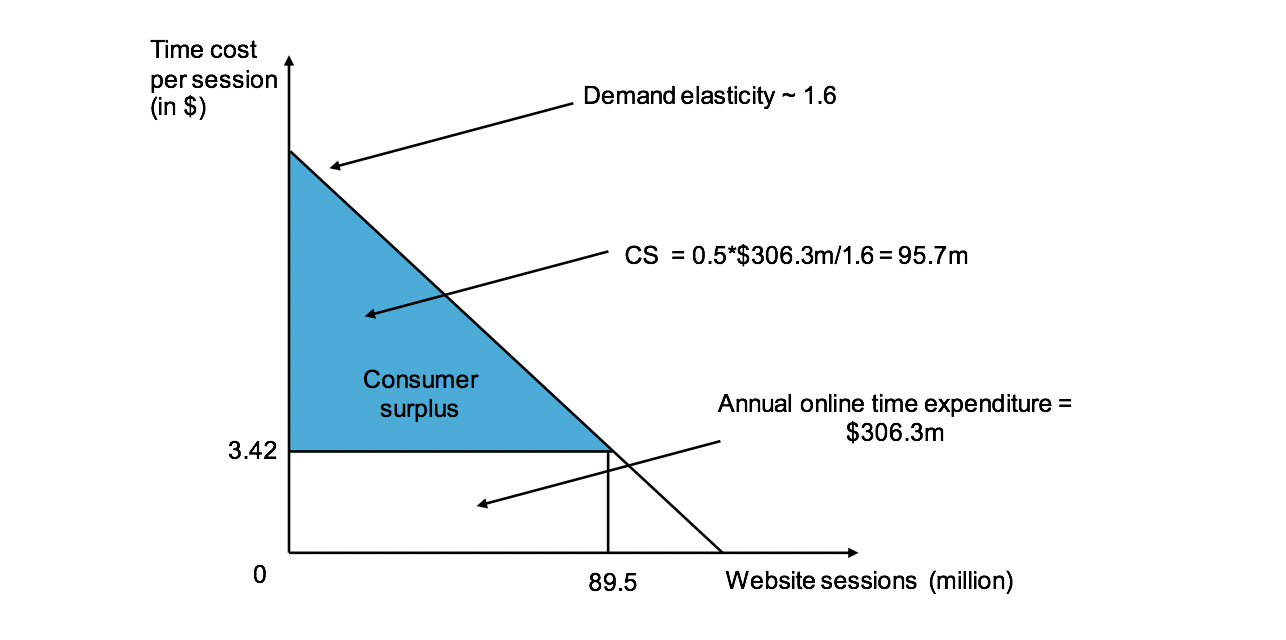

The value of GLAMs’ online content

Online visits are another way for users to interact directly with GLAMs, and so constitute another form of consumer surplus that needs to be taken into account in their total valuation. We estimate GLAMs’ online value (i.e. consumer surplus) is equivalent to $1.6 billion per annum. These results include visits to GLAMs’ official websites, catalogues and Facebook, Twitter and Instagram usage, but exclude other social media portals.

$1,440

Annual value to the average GLAMs user in improved wellbeing. As measured through the health effects of GLAMs .

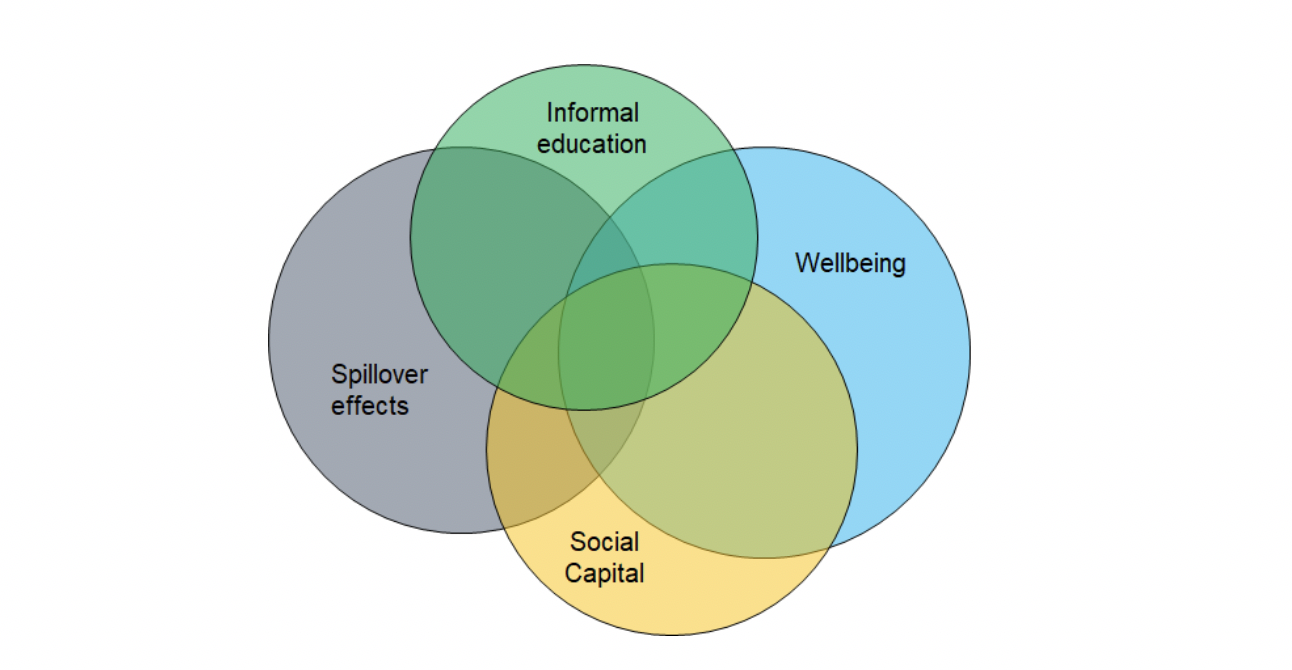

Wider benefits

Above and beyond the values described so far, GLAMs support wider benefits (“externalities”) which may not be captured by a user’s consumer surplus or other direct valuation approaches. Some of these wider benefits are difficult to incorporate into a cost-benefit analysis but are nevertheless important to recognize.

One wider benefit that we are able to quantify is the wellbeing effect of GLAMs. Regression modeling of our national survey data made it possible to provide monetary estimates of the equivalent wellbeing benefit conferred by GLAMs usage. These suggest the annual value to an average GLAM user is equivalent to $1,440 in improved wellbeing (as measured through health effects). In other words, visiting GLAMs has the same wellbeing effect of receiving a monetary bonus of $1,440 per annum.

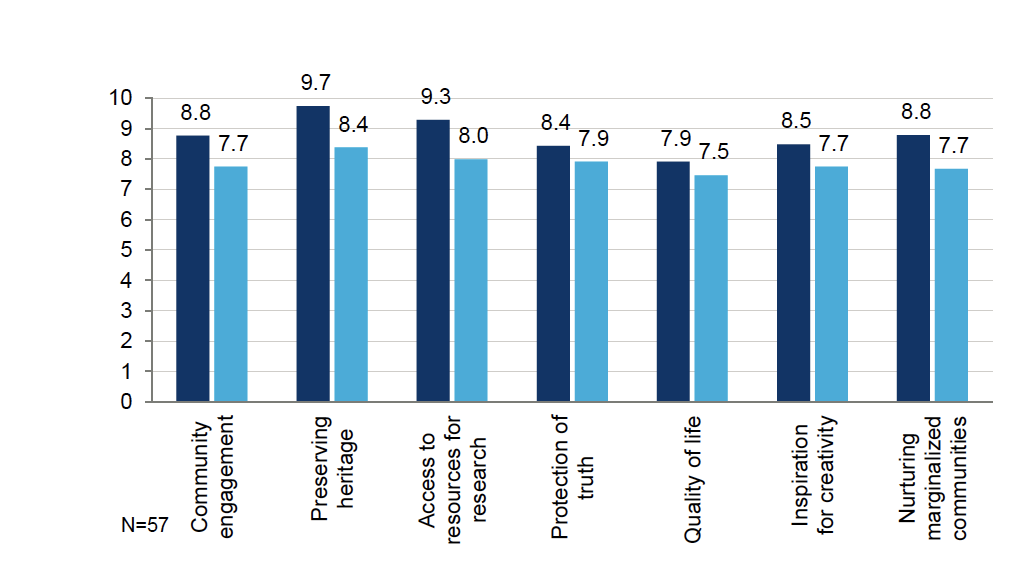

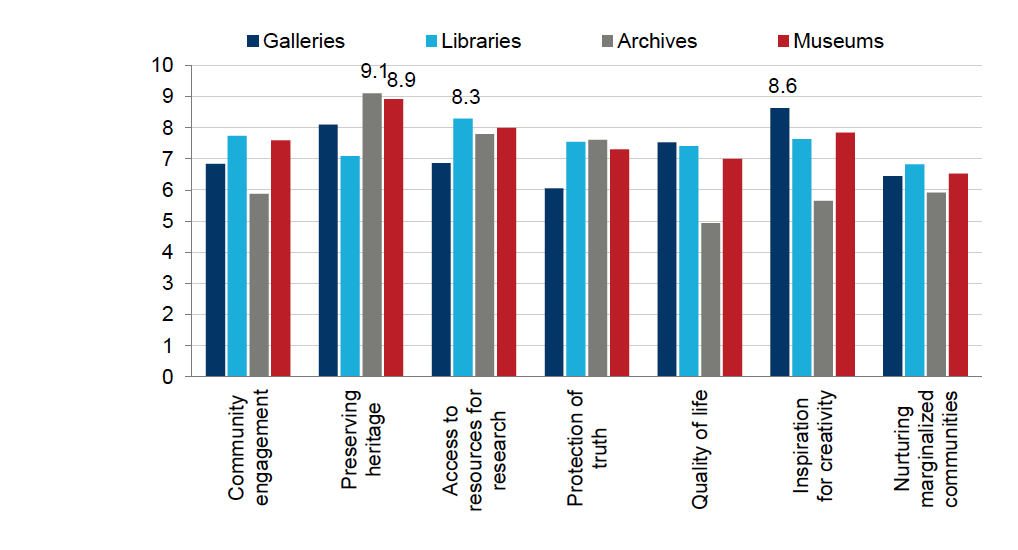

Multi-criteria analysis

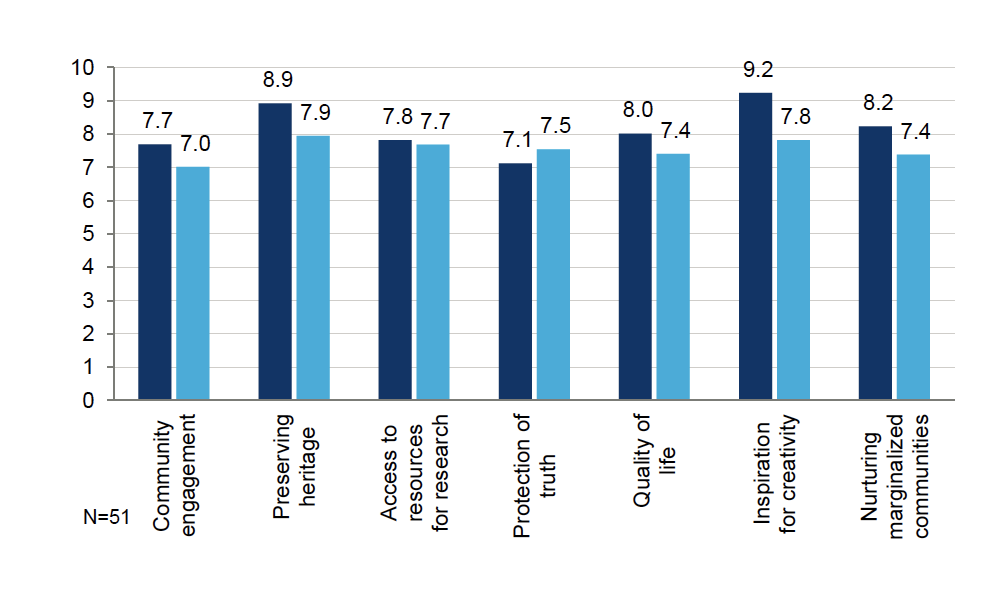

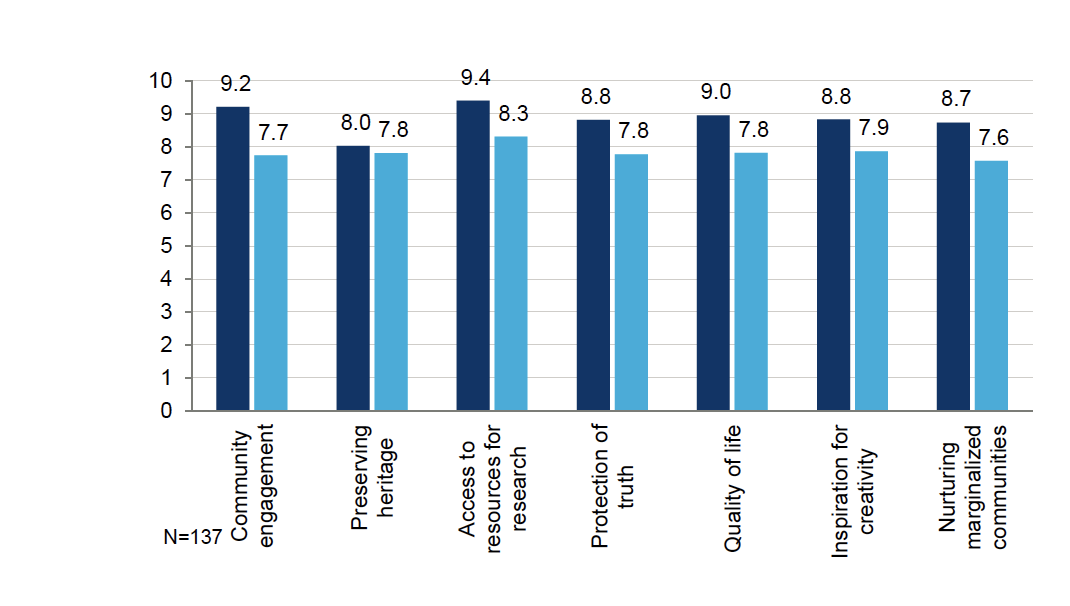

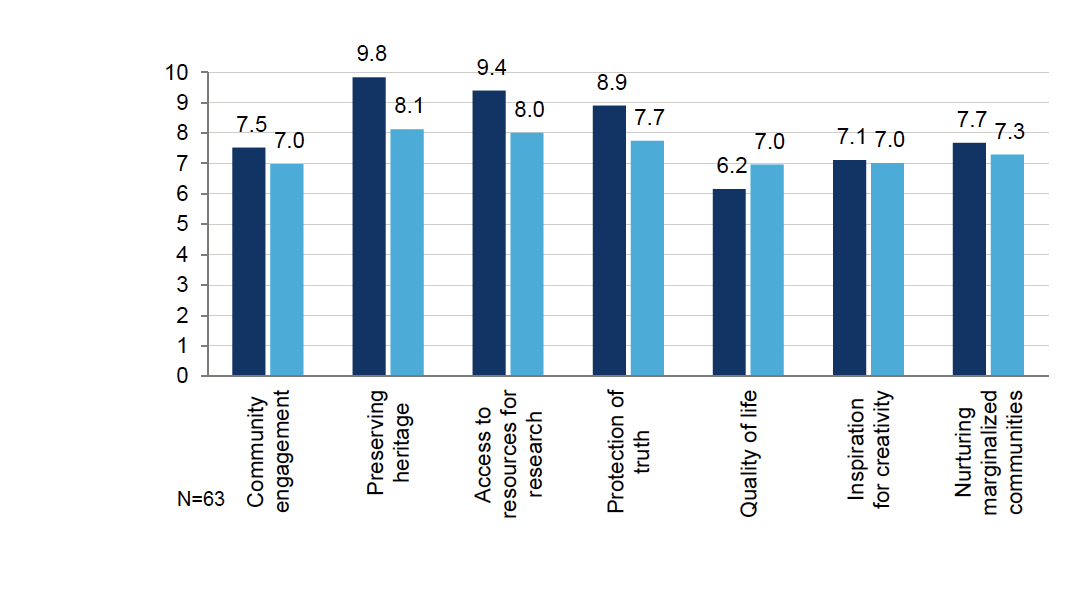

GLAMs provide intrinsic social values that economic frameworks cannot address. Accordingly, Multi-Criteria Analysis ( MCA) was also used to assess the perceived importance and degree of effectiveness of these attributes. Our MCA shows the general public and GLAM stakeholders tending to agree on which objectives matter most for GLAMs: while archives, galleries and museums play a key role in preserving Canadian heritage, libraries are crucial for access to research resources.

BCR 3.9

For every dollar invested in GLAMs, society gets back nearly four. Benefit cost ratio ( BCR) of GLAMs .

Cost-benefit analysis of GLAM

Combining all value components we were able to quantify as benefits, the total gross value of GLAMs to Canada is $11.7 billion a year (in 2019 prices). This estimated benefit was derived from annual costs (the operational expenditure needed to run GLAMs) of $3.0 billion. Dividing the $11.7 billion in benefits by the $3.0 billion of costs gives a benefit-cost ratio ( BCR) of 3.9. This means that for every dollar invested in non-profit GLAMs, society gets nearly four dollars in return. GLAMs perform very favourably when compared to other major social investments, such as transportation infrastructure.

It is also useful to highlight the net benefits of GLAMs; some prefer this approach as it indicates how much better off society is in aggregate. We estimate that society gains $8.6 billion from GLAMs’ existence every year.

| $million 2019 | Galleries | Libraries | Archives | Museums | All GLAMs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

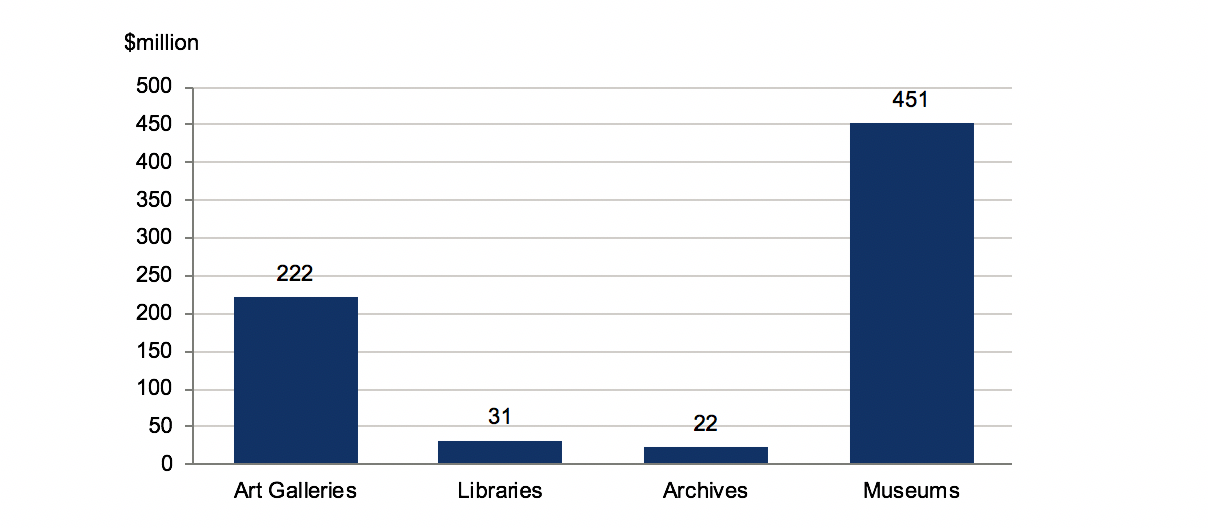

| Revenue | 222 | 31 | 22 | 451 | 727 |

| Non-use value | 536 | 537 | 446 | 693 | 2,212 |

| Use value | 615 | 1,797 | 185 | 1,374 | 3,972 |

| Online usage | 378 | 636 | 353 | 277 | 1,644 |

| Educational value | 435 | 1,361 | 41 | 1,271 | 3,108 |

| Total benefits | 2,185 | 4,362 | 1,047 | 4,067 | 11,662 |

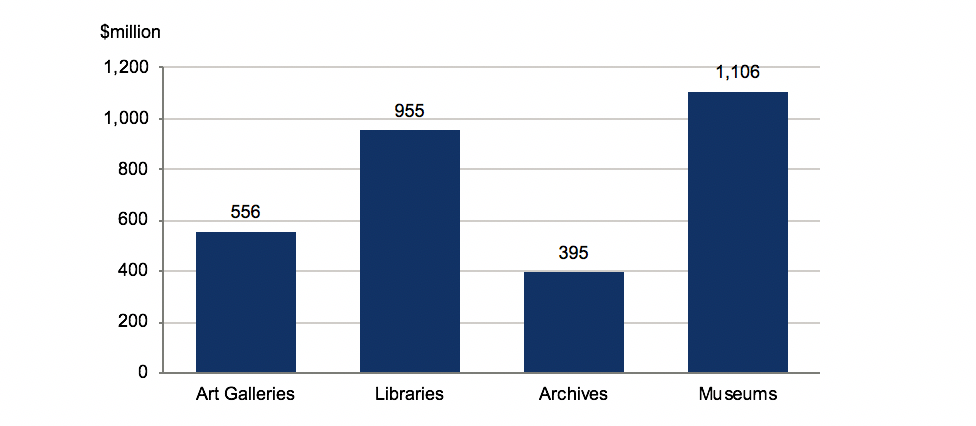

| Operating costs | 556 | 955 | 395 | 1,106 | 3,012 |

| Total costs | 556 | 955 | 395 | 1,106 | 3,012 |

| Benefit-Cost Ratio ( BCR) | 3.9 | 4.6 | 2.7 | 3.7 | 3.9 |

| Net benefits | 1,629 | 3,408 | 652 | 2,961 | 8,650 |

Glossary

- Term

- Definition

- Academic libraries

- Libraries that support the research and learning activities of students and academic researchers; normally attached to higher education institutions.

- AFA

- Alberta Foundation for the Arts.

- ALC

- Americans for Libraries Council.

- Archives

- Institutions that collect, preserve and provide access to records and documents of historical value.

- BCR

- Benefit-cost ratio. The ratio of total benefits divided by total costs. In this case, the ratio effectively represents the return on every dollar invested in GLAMs.

- CBA

- Cost-Benefit Analysis. The process through which the benefits of institutions or initiatives (such as GLAMs) are measured against their costs.

- CMA

- Canadian Museums Association.

- Consumer surplus

- The difference between the maximum amount that consumers are willing to pay to use a good or service (such as accessing GLAMs) and the actual cost of using it. This difference is treated as one measure of consumer benefit.

- CULC

- Canadian Urban Libraries Council.

- Current users

- Those who have used GLAMs within the last 12 months.

- CV

- Contingent Valuation. A survey-based technique used for assessing people’s valuation of resources that may not be captured by typical market measures—e.g. the value of GLAMs to those who do not use them.

- ESDS

- UK’s Economic and Social Data Service.

- Formal education

- Education that is delivered and/or supervised by trained teachers as part of a school, higher education or university curriculum, as opposed to informal learning.

- FSA

- Forward Sortation Areas. The first three characters of Canadian postal codes used to designate geographical areas.

- Galleries

- Institutions that select and preserve artworks and make them accessible to the public. By organizing exhibitions and programming, galleries advance the knowledge, understanding and appreciation of the arts, and help support research and inspire creativity.

- GDP

- Gross Domestic Product.

- GLAMs

- Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums.

- ICT

- Information and Communication Technology.

- Informal education

- Learning that is undertaken outside of a structured curriculum in an individual’s free time, including self-directed learning and/or learning from experience.

- LAC

- Library and Archives Canada.

- Libraries

- Institutions that provide collections of resources, especially books, used for reading and study, in addition to extensive bodies of information resources and services that may also be virtual in nature.

- MCA

- Multi-Criteria Analysis. A qualitative methodology used to provide a more holistic view of benefits. Respondents explicitly evaluate criteria used in decision-making across the key areas of interest.

- Museums

- A non-profit institution, open to the public and in the service of social development, that collects, preserves, interprets, and exhibits to the public objects of cultural, artistic, scientific, and historical value for the purposes of education, research, and enjoyment.

- Non-users

- People who have not used GLAMs within the last 12 months (or have never used them at all.)

- NPV

- Net Present Value. The net value of future benefits, less future costs, with a discount rate applied to translate these figures into today’s terms.

- ODWG

- Ottawa Declaration Working Group.

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development.

- Past users

- People who have visited Canadian GLAMs in the past, but not within the last 12 months.

- Producer surplus

- The difference between the revenue received by the producer (in this case GLAMs) and the minimum they would have been able to produce these services for. Roughly speaking, producer surplus equates to the producer’s profits.

- PSQG

- British Public Services Quality Group.

- Public libraries

- Public libraries provide free of charge resources and services to all residents of a given community or region. Public libraries are typically funded largely by public sources.

- R&D

- Research and development.

- Social capital

- Refers to the inherent value in communities that have shared and cohesive social norms, values and understandings, which in turn facilitate greater co-operation within or among groups. Social capital may arise from social activities such as community engagement, trust in people and democratic institutions, low levels of criminality and strong civic values.

- Spill-over effects

- Flow-on effects that occur when the consequences of personal or corporate actions are not fully appreciated by those involved. Positive spillover effects might include more people volunteering or being neighbourly, inspiring others to do so as well.

- TCM

- Travel Cost Method. An economic method used to estimate the value of non-market goods such as arts and culture. The technique generally involves estimating the access costs of visitors to institutions such as GLAMs (e.g. fares, time, and entrance fees) and using this to determine their consumer surplus.

- TEV

- Total Economic Value. A measure of the economic benefits of institutions such as GLAMs to the community, which includes estimation of non-use values (i.e. the value of GLAMs to society regardless of whether individuals use them or not).

- Wellbeing effects

- The broad positive feelings that can be associated with GLAMs and which can manifest themselves in ways such as positive spiritual feelings, health, happiness, inspiration and community engagement.

- WTP

- Willingness to Pay. The maximum amount in dollar terms people would pay (or give up) in order to be able to access institutions such as GLAMs. This is one measure of the value people place on GLAMs based on their personal preferences.

1. Introduction

1.1 About this study

In December 2016, the Canadian Museums Association ( CMA), in partnership with Library and Archives Canada ( LAC), held a summit in Ottawa exploring the value of Libraries, Archives and Museums ( Taking it to the Streets: Summit on the Value of Libraries, Archives and Museums in a Changing World). The summit culminated with the creation of the Ottawa Declaration Working Group ( ODWG), including a mandate to explore and study how Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums ( GLAMs) bring value to Canadian society. The Summit and Declaration were the result of concerted work by Dr. Guy Berthiaume, Librarian and Archivist of Canada, supported by LAC and CMA staff.

The ODWG was co-chaired by Dr. Berthiaume and Dr. John McAvity, Executive Director and CEO of the CMA. Dr. Berthiaume, Dr. McAvity and the ODWG continued their efforts to explore the value of GLAMs, post-summit. Accordingly, in late 2018, the CMA, on behalf of the ODWG, commissioned Oxford Economics to undertake a national study looking at the value of GLAMs in Canada. The study was made possible thanks to the financial contributions of Canadian Heritage, the McConnell Foundation and Ms. Rosamund Ivey.

Throughout this report, the term GLAMs refers to the following types of institutions:

- Non-profit, public galleries whose primary purpose is communication rather than selling;

- Non-profit, public libraries in municipalities and regions, Indigenous libraries, academic libraries at Canadian post-secondary institutions, special libraries (for example, in hospitals, museums, galleries, botanical gardens, as well as serving people with disabilities) and provincial, territorial and national libraries;

- Non-profit, public archives in municipalities and regions, Indigenous archives, archives at Canadian post-secondary institutions, and provincial, territorial and national archives; and

- Non-profit, public museums in municipalities and regions, Indigenous museums, and museums at Canadian post-secondary institutions.

1.2 Benefits of GLAMs

Canadian GLAMs receive an estimated 150 million visits every year, but they are much more than simply visitor attractions. They preserve and promote Canadian heritage domestically and around the globe, while providing access to resources that support education, research and artistic creation, and play a key role in engaging communities across Canada.

This section reviews existing literature that demonstrates the value and breadth of the social benefits of GLAMs. While there are considerable overlaps across GLAM types, we present the four institutions separately to better highlight their respective strengths. Additional details on the wider benefits of GLAMs are discussed in Chapter 8, and Appendix 4 and 5 of this report.

1.2.1 Galleries

Galleries select and preserve works and make them accessible to the public. By organizing exhibitions and programming, galleries advance the knowledge, understanding and appreciation of the arts, and help support research and inspire creativity. Furthermore, galleries offer curated content designed to increase public awareness about the role and relevance of art in the past and in today’s society.

Viewing art on laptop screens and smartphones has become more and more common over the past decade, with the exponential growth of the Internet and social media. While this can be a useful tool to access artwork in the comfort of one’s home, scholars argue that art experienced in person brings about greater social and individual benefits.

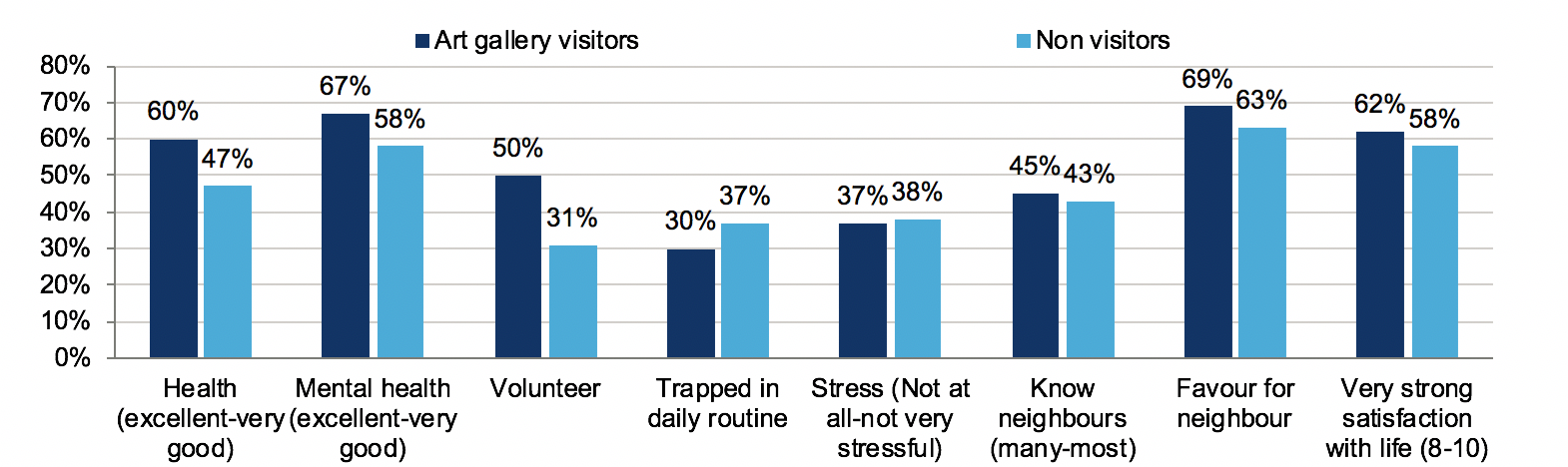

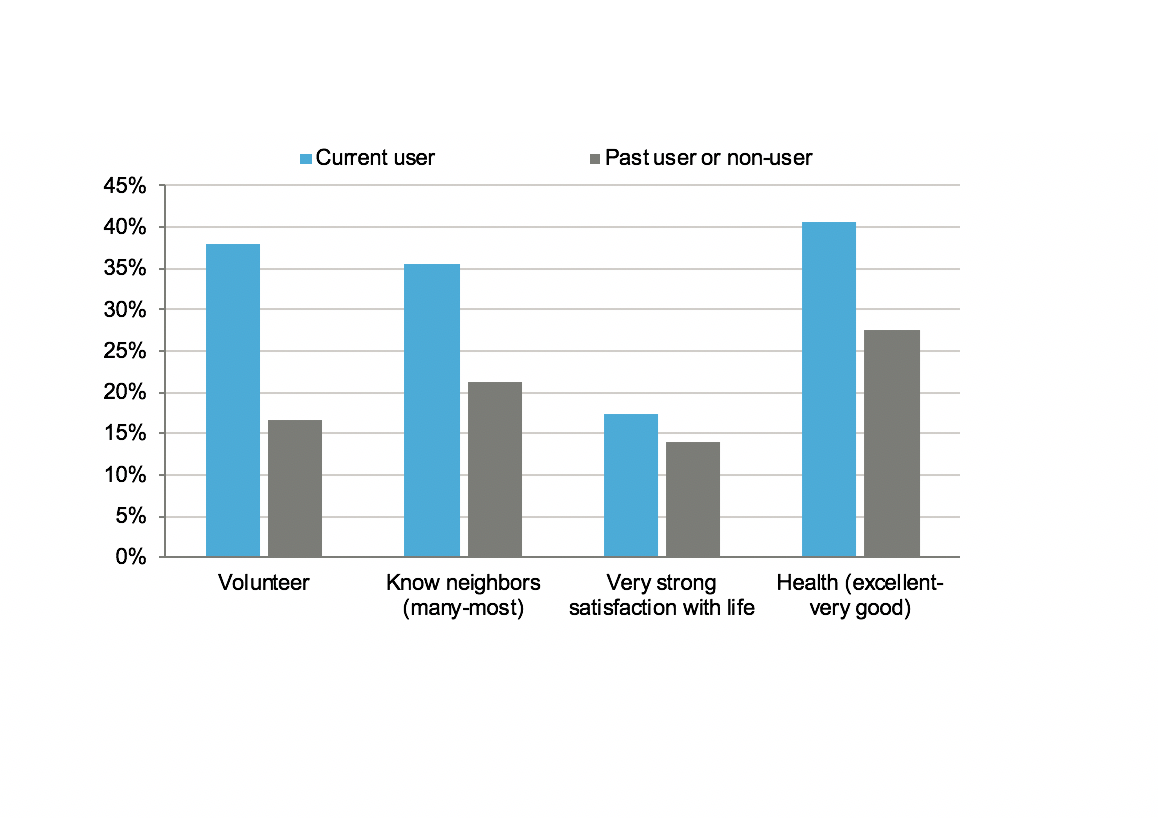

Data analysis undertaken by Hill Strategies in Canada shows that art gallery attendance has an apparent connection with several positive social indicators.Footnote 3 Fig. 2 compares gallery visitors with those who did not visit an art gallery in 2010 along a number of dimensions. Art gallery visitors were much more likely to report that they have very good or excellent health (both physical and mental) and were much more likely to volunteer.

Source: Hill Strategies

Figure description

Nevertheless, these figures did not try to control for the effect of demographic variables. Econometric models (similar to those discussed in Section 8.2 of this report) were created to inspect if gallery attendance had a relationship with individual wellbeing, above and beyond demographic features. The regression models showed that attending art galleries is linked with improved health and greater volunteer rates, even maintaining other elements unchanged (such as schooling, earnings, age, region, physical activity, etc.). In the health model, gallery visitors have a 35% higher probability of reporting very good/excellent health than non-visitors, even after controlling for other demographic characteristics. Similarly, art gallery visitors have an 89% higher probability of having volunteered in the past 12 months than non-visitors, even accounting for other factors.

More broadly, exposure to art is found to have several societal benefits.Footnote 4 Recent studies have found that life satisfaction, quality of life or happiness indicators positively correlate with participating in arts and culture activities.

One study found that participating in the arts or being an audience in the arts community is positively correlated with an increase in mental wellbeing or life satisfaction rates.Footnote 5 Earlier work also indicated that community arts programs developed social capital by increasing participants’ ability and motivation to be civically engaged.Footnote 6 This work noted that community arts programs frequently engage people from disadvantaged backgrounds (youth at risk, minorities, residents of poor neighbourhoods) and are intended for goals such as area aesthetic regeneration or teaching about multiculturalism.

In keeping with this finding, anecdotal evidence from Canada also indicates the relevance of community arts programs for youth at risk. The 2012 Calgary Power of the Arts Forum examined the example of the Calgary Antyx Community Arts, which indicates that youth use arts and culture to achieve social change. The forum included testimonials from program participants from the Calgary Youth Offender Centre and the positive effects the program created for them.Footnote 7

Likewise, a 2011 meta-study reviewed 24 articles (some of which were Canadian) of children between 3 and 16.Footnote 8 It found that partaking in organized arts activities and events enhanced secondary school attainment, early literacy skills, cognitive abilities, and transferable skills.

Lastly, a 2012 Canadian report produced by the Alberta Foundation for the Arts ( AFA) found that arts and culture contribute to flourishing and more animated neighbourhoods.Footnote 9 Maintaining a solid arts presence was deemed fundamental to sustain the wellbeing of communities and appealing to both new residents and visitors. Communities with a strong arts presence were also found to be more connected and engaged, and more likely to build positive interactions among diverse groups.

1.2.2 Libraries

Libraries are fundamental cornerstones for local communities. In addition to providing access to a wealth of resources for reading, education, and research, they help people further their skills, find jobs, and experience a strong sense of place, among many other things.

A recent study commissioned by the Arts Council of England reviewed the literature on the social and educational benefits of libraries and looked at five impact areas in detail.Footnote 10

The first impact area concerns children’s and young people’s education and personal development. Through both their core offer and targeted activities for children and young people, libraries encourage reading,Footnote 11 which, in turn, promotes language development, literacy and thus general educational attainment.Footnote 12 At the same time, libraries also directly support educational attainment.Footnote 13 Better educational attainment, in turn, leads to enhanced employability and improved health and wellbeing for children and young people as they develop.Footnote 14 Improved employability then generates economic activity and tax revenues, in turn, as well as public savings through lower welfare benefits and public health expenditure.

The second impact area is adult education, skills and employability. Through the same channels described above, libraries encourage adult reading and learning and assist job seekers.Footnote 15 These, in turn, lead to improved adult literacy and talents development, which then bring about increased levels of health, wellbeing and employability. In parallel, job seeking directly improves employability as well.Footnote 16 Better employability generates increased economic activity, public savings and increased tax income.

The third impact area has to do with health and wellbeing. By furthering reading levels among children and adults, as well as via targeted health-related activities, libraries can promote mental and physical wellbeing and sustain health service partners in supplying their services.Footnote 17 Evidence suggests that this furthers the so-called “prevention agenda,” for example via the promotion of physical activity, healthier diets, and information on the drivers of ill health.Footnote 18 As noted above, this ultimately translates into public savings.

The fourth impact area is community support and cohesion. As neighbourhood hubs, libraries offer a free, open to all and welcoming space for their local communities and service providers, in addition to making local information available for all their visitors.Footnote 19 Evidence suggests that this nurtures social capital, through higher levels of social mixing and augmented trust in people and institutions.Footnote 20

The fifth and last impact area is digital provision. Libraries sustain their communities’ digital inclusion by granting users basic access to computers connected to the Internet, as well as via targeted ICT (Information and Communication Technology) education programs.Footnote 21 This service helps to bridge the digital divide, for example through granting access to online public services and welfare provision, and through giving users the possibility to partake in online-based public and civic life. This can translate into public savings.Footnote 22

1.2.3 Archives

Archives play the fundamental role of providing evidence of past activities. Archives preserve records relating to the political, economic and social spheres of life, as well as about achievements in the arts, culture and sports, thereby helping us learn about our history and our society and increasing our sense of identity. Archives allow us to keep governments accountable for their actions, and also often help ensure that justice prevails. However, existing studies addressing the social benefits of archives are rather limited, as detailed in the rest of this section.

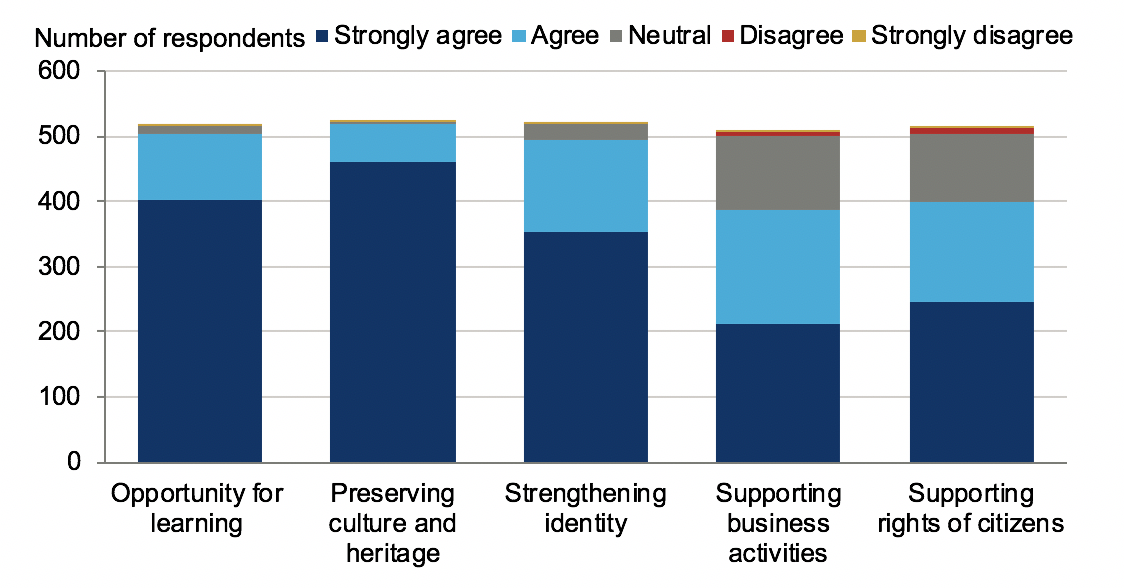

Yakel et al. (2012) analyzed data from 23 government archives in Canada, which agreed to administer a survey to every in-person visitor during a two-week period.Footnote 23 In the questionnaire, the authors asked respondents to provide their opinion of the social impact of archives based on five dimensions: opportunity for learning, preserving culture and heritage, strengthening identity, supporting business activities, and supporting the rights of citizens. The survey provided a scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree); Canadian respondents overwhelmingly agreed with all the dimensions (Fig. 3). Backing for archives as preserving culture and heritage attained the top position with an average score of 1.13, while support for business activities collected bottom place with an average score of 1.84.

Source: Yakel et al. (2012)

Figure description

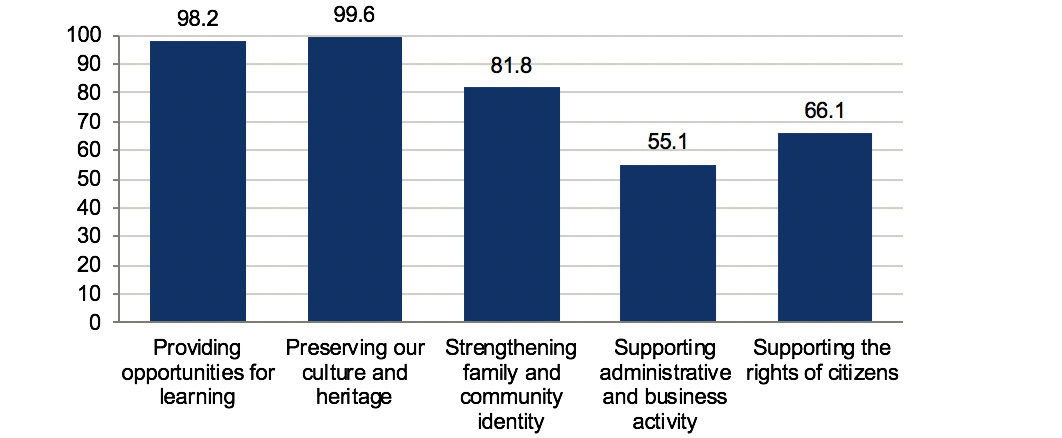

Similar results are found in the British Public Services Quality Group ( PSQG) survey of visitors to archives, which asked respondents to evaluate archives’ contribution to society along several similar dimensions (Fig. 4).

Percentage who agrees/ strongly agrees

Source: 2004 PSQG

Figure description

In addition to wide-ranging societal impacts, the 2002 PSQG survey provided further information on the perceived personal impacts on archives users (Fig. 5).Footnote 24

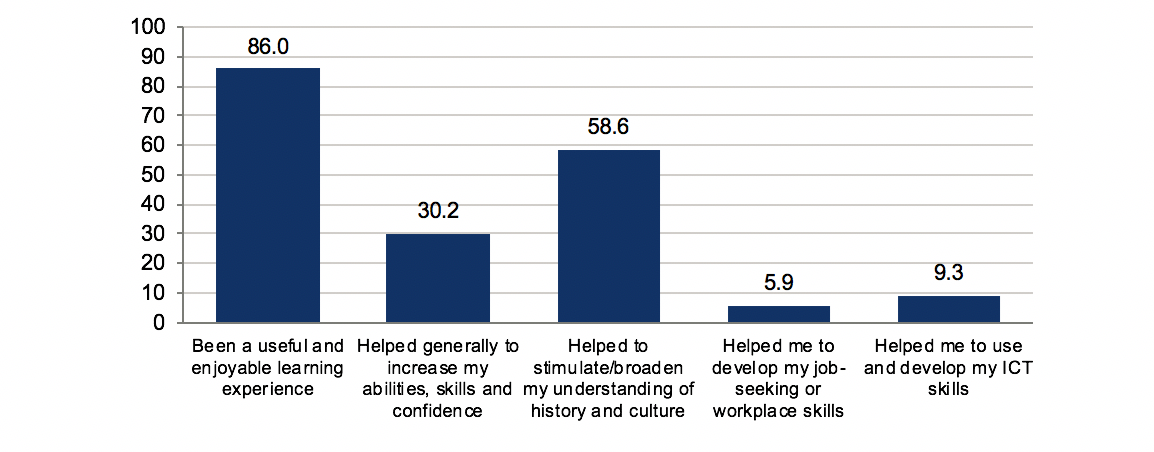

Percentage who agrees

Source: 2002 PSQG

Figure description

Lastly, UK evidence suggests that archives can make a significant contribution to the promotion of social inclusion. This happens through both the development of personal identity (several respondents highlighted the significance of evidence on births, marriages, deaths as means to maturing a sense of identity and self-confidence) and community identity (community engagement with archives can inspire not only a sense of belonging and interest in history but can also work as a promoter to civic participation).

Through their key function as providers of information in the democratic process and exercise of informed citizen’s rights, archives can also play a unique part in addressing the government objective of social inclusion.Footnote 25 Last but not least, anecdotal evidence from UK focus groups suggests that archives offer newly arrived members of a community the possibility to put down roots.Footnote 26

1.2.4 Museums

Museums have the fundamental role of narrating the story of humankind and nature over the centuries.Footnote 27 They showcase objects made by nature and by man, holding the cultural wealth of towns, cities and nations. In the early 2000s, a survey of 2,400 Canadians was launched to collect information on people’s views of museums.Footnote 28 The survey found that the vast majority of respondents thought museums play a valuable role in showcasing and explaining Canada’s artistic achievements (94%) and achievements in science and technology (96%). Some 97% believed museums play a valuable role in explaining Canada’s natural heritage, and a similar proportion thought museums play a critical role in preserving objects and knowledge of Canada’s history. These results are likely to hold true beyond Canada; for example, evidence from the UK suggests that museums hold reminders of common societal events and therefore help in constructing a communal memory.Footnote 29

The presence of original objects in museums also contributes to make them trustworthy in the eyes of their users. In their study, Conrad et al. (2009) investigate how Canadians engage the past in their day-to-day lives. As part of the data collection, they asked survey respondents to reflect on the trustworthiness of sources of information about the past.Footnote 30 Museums were rated as the single most trustworthy source by more than 40% of the respondents. Three reasons appeared to justify this choice: the availability of artefacts and primary documents; the conviction of museums’ neutrality since they are run by professionals; and the assurance derived from using multiple sources of information.

An astounding 96% of respondents to the Canadian survey on museums also reported believing that museums contribute to quality of life. This positive impact is widely acknowledged in the literature. For example, Silverman (2010) suggests that museums contribute to health and wellbeing through: (I) encouraging relaxation; (II) an instant positive change in physiology and/or feelings; (III) promoting contemplation, which can have positive effects on mental health; (IV) promoting health education; and (V) performing the role of public health advocates and improving health-care environments.Footnote 31

A prominent example of these effects is the recent art therapy program at the Museum of Fine Arts in Montreal, where doctors have started prescribing visits to the museum to people living with either mental health issues, autism or eating disorders, or with difficulties related to learning, living together and social inclusion.

Academic research on psychiatric patients also showed that museum objects might be able “to assist with counselling on issues of illness, death, loss and mourning, and to help restore dignity, respect and a sense of identity.”Footnote 32 Numerous articles also find that museum interventions have positive effects on emotional wellbeing, with reported outcomes including a sense of connection, and belonging, skills improvement, optimism, a sense of hope, and self-esteem, among others.Footnote 33 Some authors, on the other hand, have focused on museums’ role as agents to boost social inclusion and diminish socially excluding habits across communities, by offering environments and practices to re-examine conduct, manners and opinions.Footnote 34

Last, but not least, museums play a fundamental educational role for adults and children alike. Some 68% of respondents to the above survey on Canadian museums reported seeing these institutions as offering both an educational and recreational experience, in addition to the 15% who see such trips as purely educational.

Around 92% of all respondents believe it is important for children to be exposed to museums. A recent literature review found increasing proof that museum exhibitions, when supported with facilitating activities, can positively affect children’s science attitudes, teamwork, communication skills, as well as critical thinking skills in history, science, arts and humanities.Footnote 35

For instance, Burchenal and Grohe (2007) study the impact of adopting Visual Thinking Strategies (VTS), an approach used in both classroom and museum settings to promote the development of critical thinking.Footnote 36 By focusing on informal communication between a museum educator and students, VTS begin with questioning children, urging them to present supporting arguments in favour of their ideas. By carefully studying and debating artistic objects, children had the chance to relate previous experiences and knowledge to make sense of artwork on their own terms. The authors showed that the VTS method was effective at supporting the development of children’s critical thinking.

1.3 Quantifying the benefits of GLAMs

The aim of this study is to quantify the benefits of GLAMs to society, and to set these benefits in context by comparing them to the sector’s operating costs. While the costs are readily available from Canadian Heritage and Canadian Public Library statistics, quantifying the full value of all the benefits the sector generates is less straightforward.Footnote 37 To estimate them, we therefore need to deploy sophisticated analytical techniques, as explained below.

In many cases, the economic benefits or value of a company or institution can be measured in terms of market metrics such as their contributions to “Gross Domestic Product” ( GDP) and employment. But while these metrics are well recognized and understood, they represent only a part of the value generated by some types of economic activity––particularly in the case of museums and other cultural institutions. Many cultural institutions employ only small numbers of people, and their contribution to national GDP may also be small. However, their social value often far outweighs this “direct” contribution, highlighting the need for a better method of capturing the value they produce, both for society and the people who visit them.

A “Total Economic Value” ( TEV) assessment is the ideal approach for this goal.Footnote 38 Set within a framework of economic welfare (rather than a national accounts approach, which forms the basis of GDP), TEV assessments are a form of cost-benefit analysis that seeks to establish and aggregate the different values accorded to an institution or a sector by society. In the case of GLAMs, the benefits fall into two main types: direct use value and non-use value (Fig. 6). We will now consider each of these in turn.

Figure description

1.3.1 Direct use value

Direct use value is the value placed on GLAMs by the people who use them. This value is calculated based on a combination of information about the users of the services provided by GLAMs, as well as on data about the revenue generated by GLAMs from fees paid by users.

A major component of direct use value is physical use value. Conceptually, this represents the sum of visitors’ “willingness to pay” to visit GLAMs. In practice, visitors’ willingness to pay is calculated by adding together:

- the cost people actually pay for a ticket to enter GLAMs (if applicable); and

- the difference between that cost and the maximum amount visitors would have been willing to pay to visit the GLAM. This difference is known as their “consumer surplus.”

This approach is based on the assumption that people’s individual valuations of their visits typically exceed the costs they face in making them. It is thus very different from simply taking market prices as a guide to an institution’s value.

If visitors to GLAMs placed a value on their visit that was exactly equal to the cost of entry, then what they gave and received from each visit would be equivalent, and they would be indifferent between visiting or not visiting. In reality, they visit because they feel they get value from the experience that exceeds the pure cost of the visit, making the visit worthwhile. In economic welfare, this additional value is measured as the consumer surplus.

For example, a visitor may pay the $10 entry fee to visit the New Brunswick Museum in Saint John but enjoy it so much that he/she would have been prepared to visit even if the ticket price had been $15. The consumer surplus for such a person would be $5. If a second visitor is only willing to pay $12 to visit, his/her consumer surplus would be $2. In this way, consumers capture benefits over and above the prices they pay to visit GLAMs.

By calculating the visitors’ consumer surplus and adding this to the price they pay for a ticket to enter the GLAM, we can estimate the “direct use value” that visitors place on the institution.

A variety of other methods are used to calculate other aspects of direct use value such as revenue, online value and educational value, as detailed in later chapters of this study.

1.3.2 Non-use value

Non-use value accrues to people who do not visit GLAMs, but who nonetheless obtain value from it. We consider three types of non-use value:

- “existence value”—capturing the fact that many people will value the very fact that GLAMs exist, and will be willing to contribute to their maintenance, even if they have no intention of visiting them;

- “bequest value”—which captures the importance people place on the institutions as repositories of art, scientific production, historic heritage and literature for the benefit of future generations; and

- “option value”—which captures the value people place on having the option of visiting GLAMs, even if they have not visited them yet.

To a large extent, these non-use value sentiments overlap and cohere for many citizens and are therefore best considered as a group.

1.3.3 Wider benefits

As well as direct and non-use values, another category of value may be classified as wider benefits. These are values which—while potentially quantifiable—are not incorporated into the TEV for various methodological or conceptual reasons. Nonetheless their importance should be noted, and these are considered in a later chapter of this report.

1.3.4 Cost-benefit analysis

Once we have quantified all the aspects of value described above, we are able to set the social valuation of GLAMs against the costs of operating them. This process is known as cost benefit analysis ( CBA). Dividing benefits by costs allows us to establish a “benefit-cost ratio” ( BCR) for the sector, and for individual types of institutions. Put simply, a BCR above 1.0 indicates that the benefits of an investment in an initiative or institution (such as GLAMs) outweighs the costs to society. This may also be thought of as a form of return on investment (RoI) to society.Footnote 39 We can also deduct costs from benefits over time to estimate Net Present Value ( NPV).

A note on economic welfare and economic impact approaches

As indicated above, a TEV follows an economic welfare approach and includes both market and non-market impacts. This is different from an economic impact approach, which measures market-based factors such as GDP and employment and employs economic multipliers. The two overlap in some areas but start from different assumptions and measure different things.

Economic welfare is focused on returns (i.e. BCR or RoI) on a given social investment (usually the amount spent on operating costs and capital but sometimes items such as time costs) and can include market and non-market values, such as non-use value. It asks how a given initiative or institution improves economic efficiency (productivity), but also what the impact is as measured by people’s welfare in terms of things that are not always traded in markets (e.g. non-use value). So, it allows for a “decision rule” about whether a social investment is worthwhile or not (i.e. a BCR and/or NPV).Footnote 40

Impact analysis is focused on market measures such as jobs and GDP which might be of particular interest in some policy contexts. While there is some overlap, some items included in an economic welfare approach are excluded from impact analysis and vice versa. Put another way, economic impact studies measure economic activity in terms of contributions to the economy as a whole, or the share of the “economic pie” accounted for by institutions such as GLAMs. By comparison, economic welfare studies measure how society is better off in terms of net benefits (benefits less costs), i.e. how institutions such as GLAMs grow the “economic pie”. Neither is “better” than the other; they measure different things. Appendix 1 provides further details on the economic welfare approach adopted in this study.

| Included as benefit in economic welfare study? | Included as benefit in economic impact study? | Comment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Producer surplus (profit) | Yes | Yes | Part of GDP. |

| Consumer surplus | Yes | No | Not traded in a market. |

| Long term productivity effects (e.g. education) | Yes, where quantifiable | No | Impact assumes constant productivity. |

| Non-use value | Yes | No | Not traded in a market. |

| GDP | No | Yes | GDP is a key impact metric. |

| Employment | No | Yes | Employment is generally treated as part of (operating) costs under a welfare approach. |

| Provides a decision rule | Yes | No | A BCR above 1.0 indicates benefits of investment outweigh costs. |

Source: Oxford Economics

Operating costs of GLAMs

To deliver their services and programs, and to operate their facilities, GLAMs incur substantial operational and maintenance costs. These costs are paid for by public bodies (through taxes), private companies (through sponsorship), and the ticket revenues of visitors.

We estimate the GLAMs sector incurred operating expenses of $3.0 billion in 2019. More than a third of this total related to the cost of running museums, almost another third related to libraries (Fig. 8). The cost of running art galleries and archives together contributed a further third of the sector’s expenses.

Source: Canadian Heritage, Canadian Urban Libraries Council, Oxford Economics

Figure description

Operating revenues of GLAMs

The most obvious component of value created by GLAMs is the element of visitor value claimed in the form of entry and membership fees. We estimate these revenues equated to $725 million in 2019, of which the vast majority (93%) can be attributed to museums and galleries, as one would expect.

Source: Canadian Heritage, Canadian Urban Libraries Council, Oxford Economics

Figure description

Value to GLAMs’ physical visitors

4.1 Background

This chapter explores the valuation of GLAMs using an approach known as the travel cost method ( TCM). The TCM has been widely applied to the study of cultural and environmental sites across the world.

Note that the value of academic libraries is estimated separately (in Section 4.3) as a number of unique considerations apply to those institutions.

4.2 Travel cost models

A number of techniques have been used in the academic literature to estimate the “direct use” value of visitors to a cultural attraction––including simply surveying visitors, to establish how much they say they are willing to pay to visit the attraction. However, a potential drawback to this approach is that people may understate their true valuation and may think the survey foreshadows increases in ticket prices by the institution.

A well-established alternative approach is to examine visitors’ actions for clues about the value they place on the cultural institution. Methods that follow this approach are known as “revealed preference” techniques.

One such technique is to develop a “travel cost model” ( TCM). Visitors to GLAMs come from all over Canada (and the world), and the further they travel to visit the institution, the greater the travel costs they will have incurred. A TCM uses econometric analysis to exploit these patterns to understand how people’s propensity to visit GLAMs falls away as the travel costs involved increase. From this analysis, it is possible to estimate a visitor’s consumer surplus. This can then be added to the cost of a ticket to the GLAM, to calculate the visitor’s true valuation of the institution. This is the approach we have used in this study.

To develop travel cost models for GLAMs, we required information on the origins of their visitors. Several institutions collect information on visitors’ places of residence when they purchase a ticket or access a service.

A TCM is based on the insight that travelling to visit an attraction, such as a museum or a gallery, involves costs other than the formal entry fee. A visitor driving to a GLAM would face costs in terms of fuel consumption, other vehicle costs, parking costs, and the “opportunity cost” of their time spent travelling. The net value from a visit to the GLAM which remains after travel costs have been taken into account will therefore be substantially greater for someone who lives five kilometres away than for a similar person living 100 kilometres away. In our analysis, we can use these variations in travel costs as a proxy for different entry fees to GLAMs.

The degree to which visitors living further from GLAMs become more scarce allows us to infer how sensitive the typical visitor is to changes in the cost of visiting the institution. Once we understand the magnitude of this sensitivity (technically known as the “price elasticity of demand” or often just “elasticity,”) we can calculate the maximum amount that visitors would have been willing to pay to visit the GLAM. The difference between the maximum visitors would have been willing to pay and the actual access price to enter the GLAM is known as their “consumer surplus.”

For this project, we developed bespoke “Zonal Travel Cost” models for a variety of institutions.Footnote 41 A zonal model divides the country into concentric zones around the GLAM and, by observing the place of residence of visitors, determines the visit rate per number of inhabitants in each zone.Footnote 42 For example, if 200,000 visitors to the museum live in a zone defined as between 10-20 kilometres driving distance to a GLAM, and the total population in this zone is one million, then the visit rate per thousand of population is 200. The zone between 50-70 kilometres might be home to 50,000 and have a population of three million, yielding a visit rate of 17 per thousand of population. In this example, the zone that is further away exhibits a lower visit rate due to the higher costs associated with reaching the site, in line with what we would expect to see.

Based on individual GLAMs’ data on Canadian visitors’ places of origin, we were able to estimate the number of visitors coming to each institution from hundreds of Forward Sortation Areas ( FSA) around Canada. Drawing on Statistics Canada data, we were then able to identify the population living in each area, and therefore calculate visit rates. Finally, using a Google mapping algorithm, we established the travel time (and distance) from each FSA to the GLAM under consideration. To do this, we made the following simplifying assumptions:

- While all visitors to GLAMs were included in the analysis, for the purposes of assigning travel and time costs, a “day trip” cost boundary of 250 kilometres from the relevant institution was set. Trips originating within this boundary were assigned to zones as described above. Trips originating from outside the boundary were assumed to have a similar pattern of trips to those inside it and assigned to zones within the boundary accordingly.Footnote 43

- Visitors who traveled less than 2.5 kilometres walk to the GLAM.

- Visitors living further than 2.5 kilometres away can choose between driving and transit and they base their decision on the difference in travel time between these two modes of transport (if the difference is over 25 minutes, they will select driving).

These assumptions were created to mimic as closely as possible the transport mode patterns found in our national survey of the Canadian population.

For each individual GLAM, we were then able to group FSAs, visitors, and population into 10 zones for which visit rates were determined. For each zone, we estimated the total per-person travel costs, comprising:

- Direct travel costs––including fuel, maintenance, tires and parking costs of driving to GLAMs, based on information published by the Canadian Automobile Association and Parkopedia.Footnote 44 For visitors who use public transport instead, we calculated the local average fare using single ticket cash fares for adults, youth and seniors and weighting the fee based on population age patterns. Lastly, no direct travel cost is associated with walking to GLAMs.

- The value of time needed for the journey––based on standard values of time from Statistics Canada.Footnote 45 For museums and galleries, we assumed the value of time is equivalent to half the hourly salary, to reflect the leisurely nature of the activity. For libraries and archives instead, we used Canada-specific assumptions on the proportion of users who visit the institutions for work or research purposes and used the full hourly wage for these visitors.Footnote 46

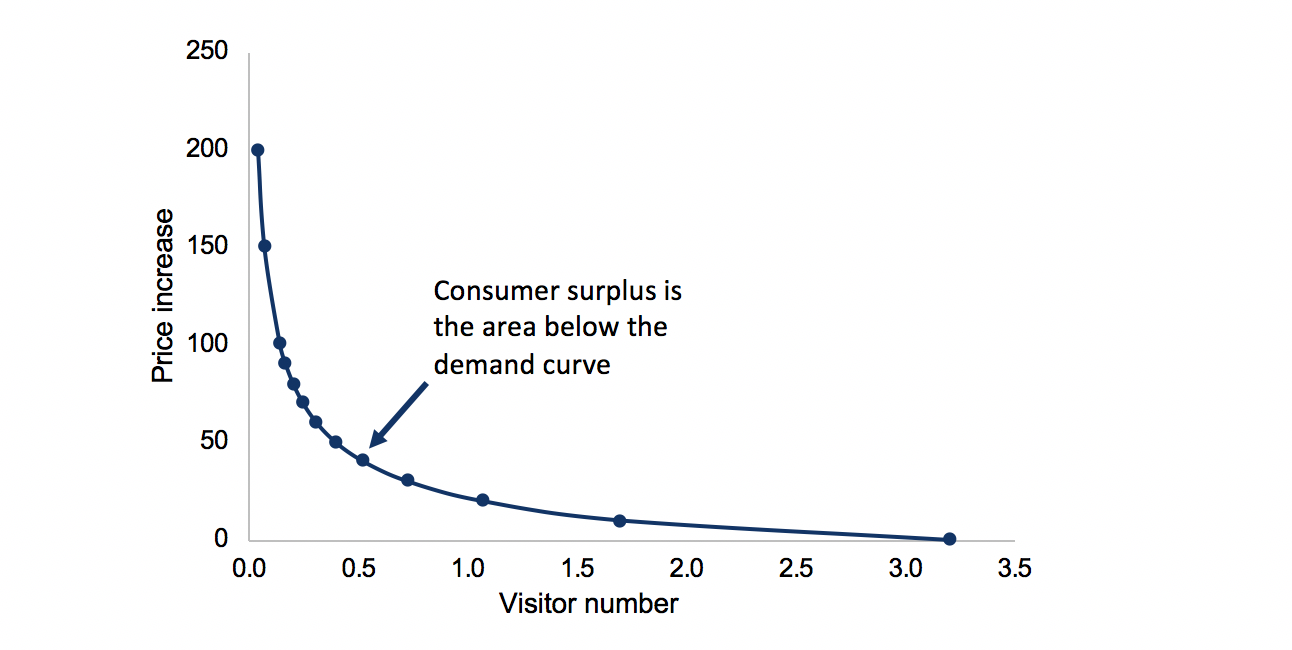

Based on these travel zones and visit rates, we were able to infer how sensitive visitors are to changes in the cost of going to GLAMs, and the maximum amount they would be willing to pay to visit an institution. When these data are displayed graphically, it is known as a demand curve. An example demand curve for visitors to GLAMs, based on a selection of simulated rises in ticket (or other access) prices, is shown in Fig. 10.

The demand curve shows that when the additional entry cost is zero (i.e. the entry cost is the same as at present) there are as many visits as there are at present. As the entry cost increases, the number of visits declines. While the number of visitors is initially very sensitive to small changes in the cost of visiting GLAMs (at the right-hand end of the curve), the degree of sensitivity (or “elasticity”) declines as the additional cost increases. For example, an increase in the additional cost of a visit from zero to $10 would be expected to approximately halve the number of visitors, whereas further increases in the additional cost would have a much smaller impact on visitor numbers.

Source: Oxford Economics

Figure description

Estimation of demand curves therefore offers a powerful tool for GLAMs analysis. These curves provide information on how much people value GLAMs and how many people would be willing to use them at different price levels. This could be of particular interest to ticketed venues, but also in situations where access conditions change for all venues (e.g. it becomes more/less costly to access GLAMs).

Moreover, the demand curve incorporates people’s preferences to use GLAMs for whatever purpose they choose (e.g. reading books, researching jobs, viewing art). It also incorporates people’s preferences to use GLAMs rather than pursue alternatives. For example, people may use public libraries, which have no entry fee, but if there was such an entry fee, they may seek alternatives (e.g. buying books).

The demand curve’s shape, as measured by its sensitivity to price changes (or elasticity) tells us how appealing GLAMs are against those other alternatives, and what would happen if indeed such a fee was levied. In doing so, it shows us how people may trade off the use of their resources (time and money) and so provide the key to valuing GLAMs.

The demand curve can also be used to estimate the consumer surplus of GLAMs visitors by looking at the impact on visitor numbers from different simulated increases in the cost of visiting. In essence, the total area underneath the demand curve is equal to the difference between the actual cost and the maximum amount visitors would have been willing to pay to visit the institution. This is the consumer’s “profit” or consumer surplus as discussed above.Footnote 47 The various models yield a range of consumer surplus estimates, which vary both by the type of institution, but also by the geographical location and the size of the institution (urban vs. rural, small vs. large, etc.).

In addition to individual GLAMs’ travel cost models, we also developed “supermodels” (national models) from the national survey for each institution category. These national models offer a “top down” approach using national survey data, as opposed to the “bottom up” approach using the behavioural data drawn from the various GLAMs. The national models cover a much broader sweep of the population and so are a useful complement to the individual bottom up models. Another important feature of these differing modelling approaches is that the national models use people’s reported travel costs (along with the defined values of time developed above). The national models therefore reflect perceived travel costs, whereas the bottom up models reflect what is sometimes referred to as “researcher defined costs.”Footnote 48

For museums and galleries, combining bottom up results with our national model ones suggests that the average value of each visit is $44. Canadian Heritage 2015 data (the latest available) suggest a total of 45.6 million visits to non-profit galleries and museums in Canada; 31.5 million to museums and 14.1 million to galleries.Footnote 49 Multiplying the consumer surplus of each visit by the total number of visits provides an estimate for the total value of Canadian galleries and museums to their users. Our estimates suggest that galleries and museums generate a total annual consumer surplus of $2.0 billion.

For archives, visitation data are more limited, as the area is less well studied. However, we were able to overcome this to some extent by gaining access to supplementary data. Our estimates relied on four main sources. We utilized information from (1) the University of New Brunswick’s Archives & Special Collections and (2) Ontario Archives, as well as (3) developing a “supermodel” (national model) from the survey results. As a fourth and last data source, we obtained visitor origin data from the archive visitor survey undertaken by Yakel et al. (2012).Footnote 50 This included 468 usable responses on visits to 23 Canadian archives, nationwide. This last source would appear to represent one of the richest available data sources on archival visits in the world.

Combining the four models, we estimate a consumer surplus of $65 per visit or $185 million nationally. Evidence suggests archives’ in-person visitors are likely to be particularly determined—especially given the increasing availability of online access.Footnote 51 This helps explain the much greater consumer surplus per visit we identified.

Lastly, for libraries, we have sourced data to develop TCMs for the Hamilton, Kitchener, Regina, and Vancouver Public Libraries. We also supplemented this with a “supermodel” (national model) drawn from the national survey results. Combining these two suggests a consumer surplus/visit of $18. Multiplying this figure by the total visits to public libraries from the Canadian Urban Libraries Council (hereafter, CULC), scaled up to include all public libraries, yields a total value of $1.8 billion per year.Footnote 52 The figure below provides a summary of physical use values.

| Item | Galleries | Libraries | Archives | Museums | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average physical use value per visit $(1) | 43.6 | 17.6 | 65.2 | 43.6 | |

| Estimated visits 2019 (million) (2) | 14.1 | 102.2 | 2.8 | 31.5 | |

| Physical use value $(million) (3) = (1) * (2) | 615 | 1,797 | 185 | 1,374 | 3,972 |

Source: Oxford Economics

All figures subject to rounding

4.3 Academic libraries

The discussion above relates to the estimation of the value of physical visits to GLAMs including public libraries. However, it does not include estimations of visits to academic libraries. Academic libraries have a different usage base, purpose and character to public libraries.

In addition, many of their users are students and some students live on campus. The students who live on campus do so because that is where they have gone to be taught and to use campus facilities—including the library. This creates what is technically known as an “endogeneity problem”—the users’ choice of living location is not independent of the facility they are using but is at least in part governed by it. The TCM generally assumes that the choice of living location is “exogenous” or independent of the facility—e.g. we assume that most users of galleries do not deliberately live close to an art gallery (though of course in a broad sense, the gallery may be one of many things that attracted them to live in a town or city).

Another issue is that many of the benefits of academic libraries are educational and educational benefits may only play out in the long term.

Therefore, we have not used the TCM to measure the benefits of academic libraries but instead have chosen a different approach. There have been many attempts to measure the value of academic libraries. Many of these focus on measures such as student retention and/or superior academic performance as a result of high usage of academic libraries.Footnote 53 However, these may only capture part of the benefits of academic libraries. For example, high usage of academic libraries may improve student grades but all students (including low usage students) may ultimately get a benefit.

Academic libraries are effectively embedded in university education. Accordingly, the approach adopted in this study is to see academic libraries as a part of the broader benefits offered by a tertiary education over the long term.Footnote 54 If that is the case, then academic libraries would account for a share of student benefits from such an education. Of course, faculty also use these institutions and an allowance is also made for the benefits of faculty usage of such facilities. The approach taken is detailed in the box below. This approach suggests a BCR for academic libraries of about 3.4, with an NPV of $3.4 billion.

Because of their quite different character, we have nonetheless separated out results for academic libraries from public libraries, as some may feel mixing these in with public libraries reduces transparency and may blur the quite distinctive character of each institution. The main BCR and NPV results presented in the Executive Summary and Conclusion therefore only detail public library results (i.e. exclude academic libraries).

Assessing the value of academic libraries

The approach to the estimation of academic libraries was based on estimation of the long term returns to university education in Canada. Academic libraries are part of a mix of learning that occurs in universities and so would be expected to be responsible for a share of the benefits. Given data on the return to university education in Canada, and attribution of library share of costs, this allows for the calculation of a BCR and NPV for student usage. In addition, allowance can also be made for academic usage to estimate a combined total.

Students

The following approach was adopted to assess benefits from student usage:

- Data sourced from the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development ( OECD) was used to calculate the total social costs and benefits of a Canadian university degree over the working lifetime of students.Footnote 55 These include both the private costs and benefits (e.g. fees, employment income forgone, higher future wages) and public ones (government subsidies, future tax income).

- Based on OECD data, the present value of costs is $89,249 and that of benefits is $297,764 over the lifetime of a typical Canadian student.Footnote 56 This equates to a 3.3 BCR, which implies the social benefits of a Canadian university degree are 3.3 times the costs.

- The next question is how to apply these results to academic libraries. Given that benefits are 3.3 times costs, there is a need to estimate library costs. Data from the Canadian Association of Research Libraries (hereafter, CARL) was used to estimate academic library running costs (an adjusted $737 million in 2016-17).Footnote 57

- However, the benefits cited above result from society incurring not just direct costs (running costs recorded by CARL) but indirect ones (forgone income while studying).

- Based on the estimates above, we calculate that indirect costs account for 47% of total social costs. Accordingly, total social costs attributable to CARL libraries were assessed at approximately $1.4 billion per annum.

- Given a BCR of 3.3, this suggests total social benefits of $4.7 billion from academic libraries and an NPV of $3.3 billion.

Faculty

Faculty benefits were determined based on the work of King & Tenopir (2008).Footnote 58

- King and Tenopir undertook contingent valuation work in five US universities finding that scholarly journal usage is by far the most common academic library activity undertaken by faculty. Accordingly, their study concentrates on the annual usage of scholarly journals in academic libraries.

- This work is in some ways a parallel to the student benefits above. It incorporates both private access costs (annual faculty wage costs of $US 704 per person) along with costs to libraries of purchasing and maintaining journal collections ($US 1,052 per faculty member in total). It also includes the benefits of usage, given the cost of obtaining the data from alternative sources ($US 3,466 per faculty member per annum).Footnote 59 A BCR of 3.3 is recorded.

- Since the costs of journal collections are already included in the student usage above, only the academic faculty time costs are included in the calculations for the current study.

- The number of academics at CARL institutions was estimated based on CARL data indicating 845,782 students at these institutions and using an average student faculty ratio of 20.Footnote 60 These calculations produce a total of 42,289 academics at CARL member universities. Adjusting the 2008 $US faculty values to 2019 Canadian values, in turn, suggests $216 million in annual benefits and $43.9 million in costs for academic library usage by faculty (excluding library running costs).Footnote 61

Results

The combined results from the student and faculty estimates above suggest that the total benefits equate to $4.9 billion and total costs to $1.4 billion in present value terms. This suggests a BCR of 3.4 for academic libraries (and a net present value of $3.4 billion). Note this result largely reflects the long-term benefits of these libraries as they contribute to higher student wages and government income over the working lifetime of students.

Non-use value

5.1 Background

In assessing the value of GLAMs, it is important to pay attention not only to their direct usage but to a broader set of values above and beyond such usage. Whether or not they use GLAMs, people may value them simply for “being there”—i.e. the fact that GLAMs exist and it is good that society does these sorts of things. Or they may see value in ensuring GLAMs are preserved for future generations. Or perhaps they wish to use GLAMs “one day” and want to keep that option open.

This collection of values is often known as “non-use value” or “passive use value.” Non-use value is in fact fairly intuitive; societies are prepared to subsidize a range of activities over the longer term. Apart from the arts, another example might be subsidies for services in remote communities. Most people would not be citizens of such communities, or ever expect to use these services. Nonetheless, they might be happy to fund such services on equity or other grounds. They might see such subsidization as part of what society does. Likewise, society’s willingness to subsidize cultural assets over the longer term may be seen as an implicit indication of non-use value.

Non-use value is commonly estimated for environmental or cultural amenities, which are often seen as intrinsically valuable by citizens. Past studies have found that non-use values can account for a substantial proportion of the benefits of a cultural or environmental asset.

In the case of GLAMs, non-use value can be seen as consisting of three different components:

- Existence value—The value people attach to the existence of GLAMs despite the fact that they may have no intention of visiting them.

- Bequest value—The value that people place on GLAMs as a benefit to future generations.

- Option value—The value people attach to having the option of visiting GLAMs at some point, whether or not they ever exercise that option.

In practice, people may have a mix of all three of these components in mind when assessing non-use values in situations such as those discussed in our national survey and it may be difficult to disentangle one from the other.

The importance of non-use value to cultural institutions has been demonstrated in jurisdictions such as Detroit, where voters, the private sector and government acted to prevent the sale of part of the collection of the Detroit Institute of the Arts (DIA) during a time of financial crisis. This involved providing over $US 800 million in funding under what came to be known as the “Grand Bargain.” Given that the majority of the public were unlikely to be users of the facility, the fact that society was willing to pay such amounts to retain its art collection during a time of financial crisis provides a “real world” example of the role of non-use value in respect of cultural assets.Footnote 62

Non-use value can be measured through the use of a public survey, employing a survey technique known as contingent valuation ( CV). A CV assessment was carried out as a part of the national GLAMs survey described above.

5.2 National survey

By definition, non-use value is not traded within a market, since it relates to the way people value something they do not directly pay for or use. So, in order to measure non-use value for GLAMs, a national survey of the general population had to be conducted. The established approach for such surveys is to focus on people’s “willingness to pay” ( WTP) for cultural assets and this was followed here.

As indicated, WTP questions were therefore incorporated into the online national survey of the Canadian population, described above.Footnote 63 Survey quotas were imposed by sex, age, education, language (English/French) and province or territory of residence in order to ensure a broadly representative sample of the Canadian population. A total of 2,045 completed responses were received from Canadian residents. The survey questionnaire was informed by recent literature on contingent valuation approaches.Footnote 64

The national survey included current users of GLAMs (i.e. those who had used such facilities within the last 12 months), as well as non-users (i.e. those who had not used GLAMs within the last 12 months or had never used them at all). The non-users are of particular interest here, since they could value GLAMs even though they do not use them. This can be interpreted as a sign of society’s underlying non-use value for GLAMs (across both current users and non-users).

The survey results were then used to assess WTP across the various institutions and GLAMs as a whole. The approach to doing so is described in the box below.

Assessing the non-use value of GLAMs

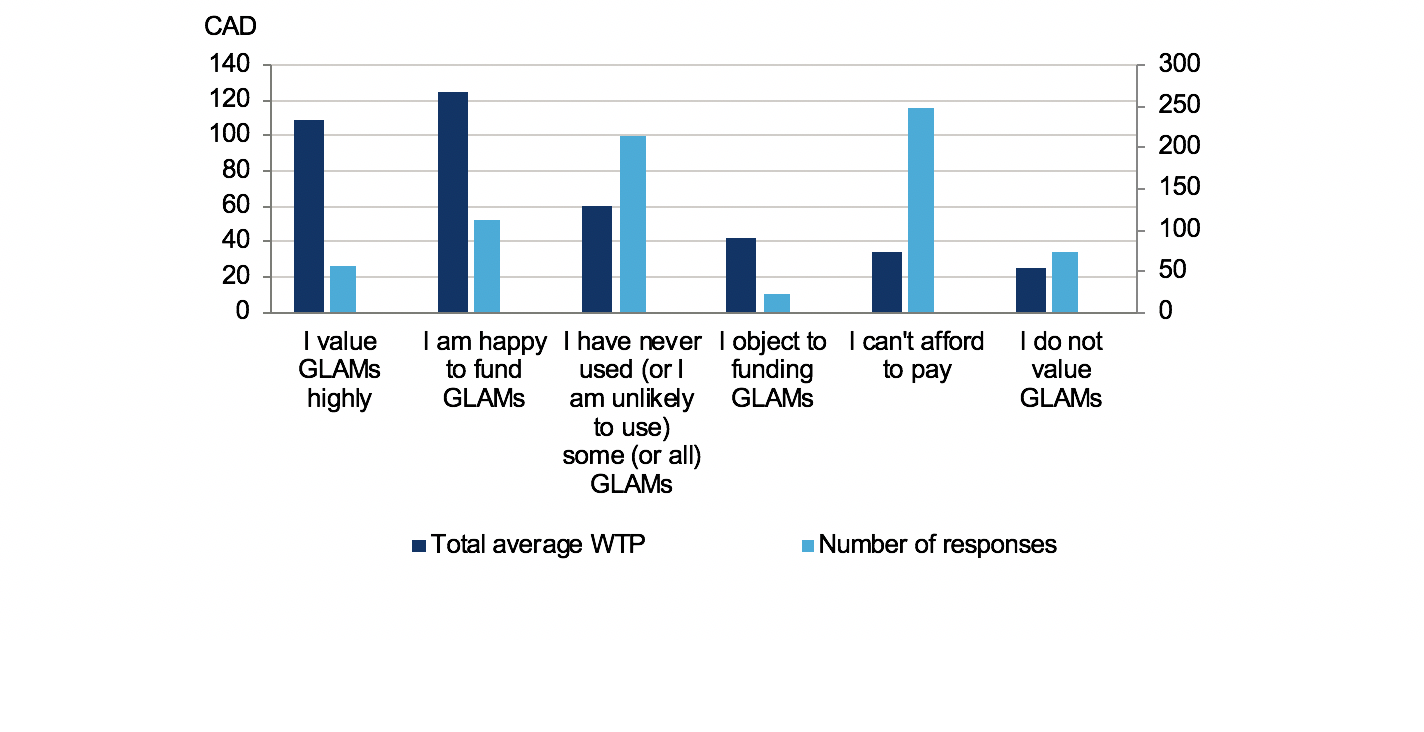

The national survey asked all respondents (i.e. both current users and non-users) about their willingness to pay ( WTP) for the four defined types of GLAMs.Footnote 65

Care needs to be taken in setting questions about cultural resources such as GLAMs. Analysts need to bear in mind the fact that unlike goods that people buy on an everyday basis (e.g. grocery shopping) people are not always familiar with the “price” of the resource in question. In addition, there is the risk of people providing very high WTP responses because “talk is cheap” (“hypothetical bias”) or saying they would pay too little because they think they might be saddled with new taxes or charges (“strategic bias”) and/or the word “tax” setting off in principle objections (“protest votes.”) Although some academics suggest providing the cost of the service to respondents (e.g. public spending per GLAM), other analysts also point to “anchoring” as a form of bias—where respondents latch on to the value provided by the questionnaire.

In order to ameliorate some of these potential biases, respondents were provided with brief information about the contribution GLAMs make to society. They were then asked if they would be willing to make a donation to support GLAMs across the country in the event that public funding was withdrawn. A short form of the WTP question is below. (The full question is included in the questionnaire, located in Appendix 6)

In one way or another, all Canadians currently pay towards the annual upkeep and development of galleries, libraries, archives and museums ( GLAMs) whether through taxes, donations, entry fees or other means. However, imagine that GLAMs had no other sources of government or private funding and the only way of maintaining them was to rely on individual donations. In such a situation, what is the maximum amount you would be willing to pay each year as a donation to maintain all of Canada’s non-profit GLAMs?

Respondents were then asked to consider how much they would be willing to pay given various price options, but they could also freely select a value of their own if they wished to.Footnote 66

Respondents were reminded of the fact that they had limited budget to pay for GLAMs in addition to their everyday spending. In addition, the online survey allowed respondents to see how their WTP for each institution added up to a total for all GLAMs as another counter to overestimating WTP. All 2,045 respondents were required to provide values for this section of the survey.

Source: Oxford Economics

Figure description

As indicated in Fig. 12 above, current users tended to have higher valuations than non-users. This is in line with expectations and would reflect the fact that such respondents may be mixing their use values with broader non-use values held across society.